Can a garden plant connect us to a past so unimaginably distant that Earth itself was unrecognizable?

If we interrupt our routines, just for a moment, we can consider a plant that links us to an ancient time. Osmunda claytoniana, commonly known as “Interrupted Fern,” looks perfectly at home in a modern garden, yet it is essentially the same plant it was over 200 million years ago! Even before the first T-rex appeared, Interrupted Fern inhabited lush woodlands on proto-continents that later splintered, collided, and drifted apart.

A fossil found in Antarctica tells the story. In the late Triassic period (252-201 million years ago), the land mass that is now Antarctica had a temperate climate. There, growing near a stream in a shady forest, an Interrupted Fern became encased in sediment and then fossilized. The fossil reveals a plant that is virtually indistinguishable from Interrupted Ferns growing in gardens and forests in the Northeastern US today! Most plant and animal species found on Earth in the Triassic became extinct millions of years ago. Of those that survived, most have undergone so many mutations and evolutionary changes that they are virtually unrecognizable. But Interrupted Fern has continued – essentially without interruption!

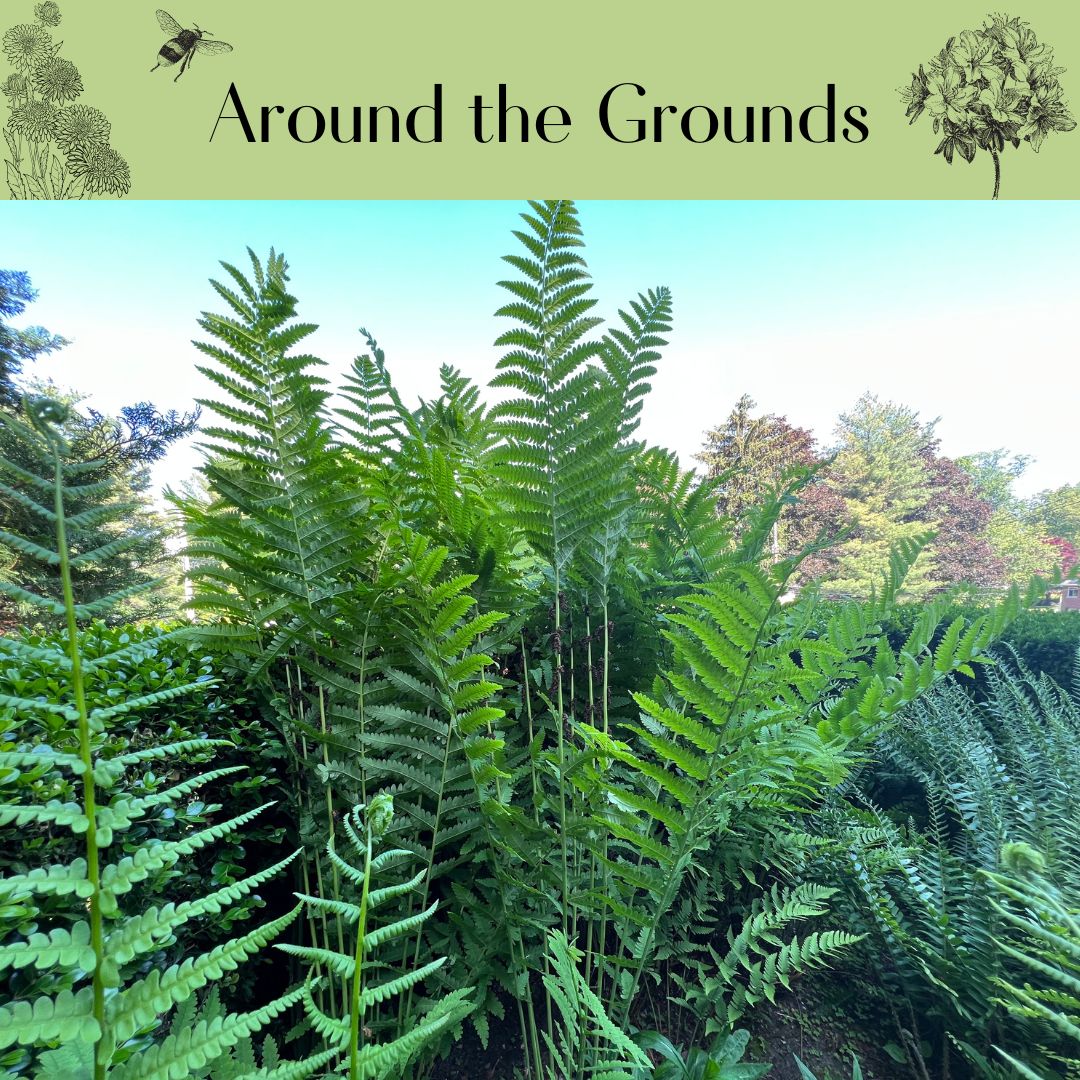

Osmunda claytoniana is called “Interrupted Fern” because of its unusual and readily-identifiable structure. While most ferns carry their spores on separate stems or on the undersides of leaves, Interrupted Fern sends up fertile spore-bearing fronds from the center of the plant with feather-like clusters of “sporangia” in mid-stem. As the spore clusters ripen and drop away, the mid-section of the frond is “interrupted” leaving bare space between the leaves.

Interrupted Fern is a great landscape plant. It emerges in early spring and remains fresh and upright throughout the summer, making an architectural statement in the garden. The fronds typically reach about 3 feet in height, and form an attractive vase shape. The fern expands its territory from the rhizome slowly, over a decade or so, eventually forming a clump. Once established, a clump of Interrupted Fern can be very long-lived. Thriving examples have been found in gardens abandoned for over fifty years. A colony of a naturally-occurring hybrid between Interrupted Fern and its close relative, Royal Fern, in Virginia is thought to be about 1,100 years old.

Though it once lived in Antarctica, Interrupted Fern is found today only in Eastern and Central US and Canada. It does best in rich, moderately damp acid soil in full to part shade, but it grows taller (4-5 feet!) with more sun. Hardy in Zones 3 to 7, it is not palatable to deer – or dinosaurs, apparently. It provides cover to small birds and mammals, and makes an excellent underplanting for trees, especially at the edges of wooded areas where leaves are allowed to remain in place, enriching the soil.

Interrupted Fern dies back to the ground in late fall, leaving a mounded crown at the surface of the soil and a network of fine roots below. The rhizome can be dug for transplanting with a sharp spade in early spring by cutting the roots 4 to 6 inches from the crown and settling the crown in the new spot at the same height, spreading the roots out under a light layer of soil. Leaf mulch or compost are much better than bark mulch for keeping the soil moist and cool. In spring, the fronds emerge covered with long, fuzzy hairs and unfurl over a week or so. Once established in a suitable spot, Interrupted Fern really needs nothing more from humans!

As we worry about climate change, destruction of habitat, and the alarming loss of plant and animal species in what scientists are calling the “Sixth Great Extinction,” there is some comfort in observing this lovely plant that has seen more than one apocalypse and managed to survive unchanged. This ancient fern may just survive it all.