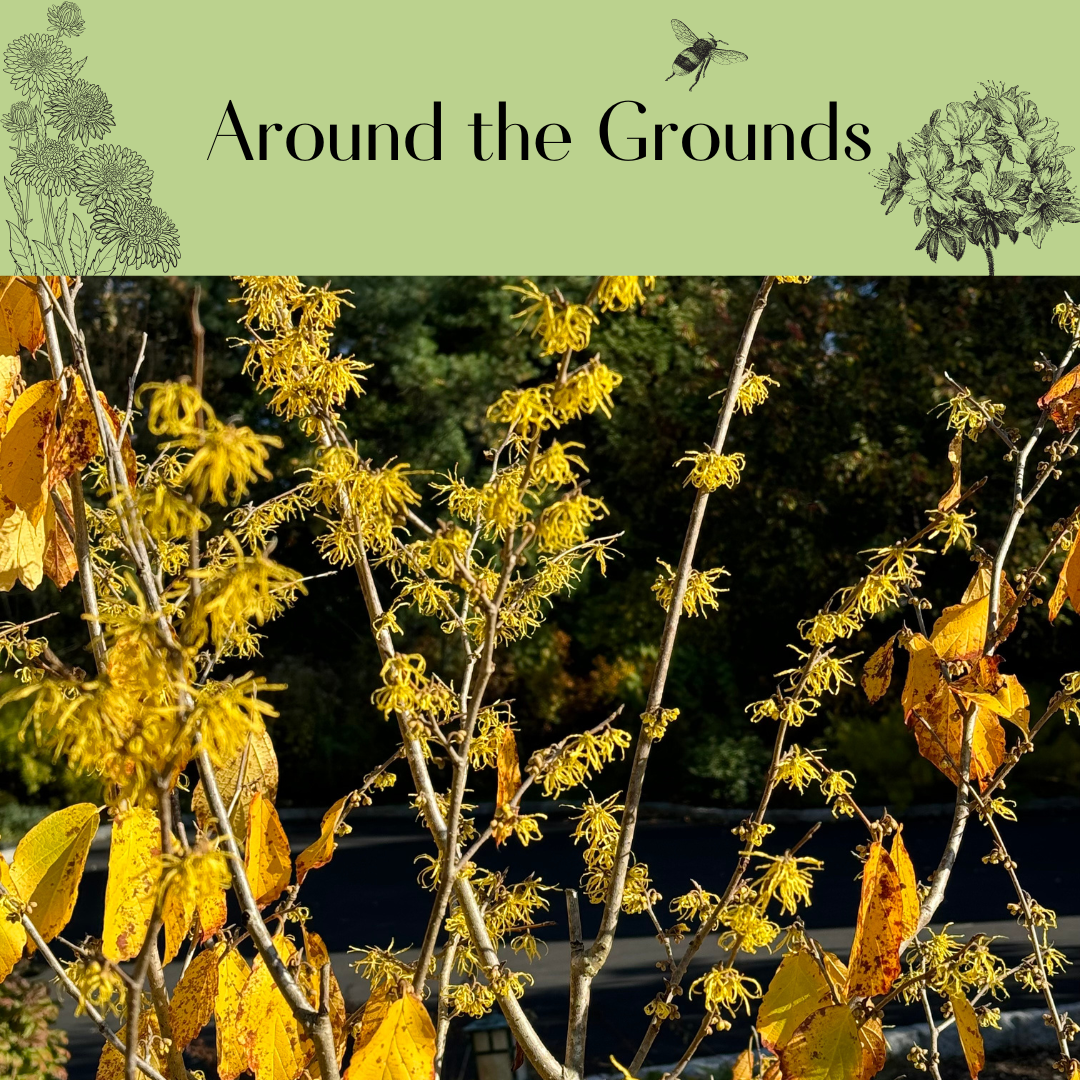

After Halloween and a little before Thanksgiving, Witch-hazel (Hamemelis virginiana) starts blooming. It’s always a surprise to see its bright yellow flowers appear just as fall colors fade and branches are bare.

Witch-hazel is a fascinating plant. It’s a multi-trunked shrub or small tree that evolved as an understory plant in the forests of the Northeastern US. You might not notice it at all in the spring or summer when it sits modestly under bigger trees in part shade. But in early winter, when most plants are going to sleep, Witch-hazel is hard to miss. Its flowers are fragrant, and adorned with tiny yellow streamers reaching out in all directions.

The leaves, bark, and twigs of Witch-hazel contain tannins and flavonoids that Native Americans used for centuries to treat skin ailments. European colonists soon adopted the practice, and today Witch-hazel is one of the few plants the Food and Drug Administration has approved for use in over-the-counter products. Many cosmetics companies use Witch-hazel in toners, diaper rash remedies, acne treatments, pore reducers, and after-shaves.

A more questionable early use of Witch-hazel was the practice of using forked branches as dowsing or divining rods to search for underground water. A “water witch” would hold the forked end of a Witch-hazel branch and walk until the flexible tip supposedly dipped when underground water was detected. Dowsing with Witch-hazel branches for well-digging was a common practice right into the 20th century.

insect-pollinated plants.

The real mystery of this plant still isn’t settled. Why does Witch-hazel start blooming in winter when most pollinators are already hibernating? And which insects do pollinate the flowers? Some researchers have pointed to a moth species that survives freezing temperatures by shivering so hard that its body is actually warmer than surrounding air temperature. Others have suggested that a small and very late-acting bee is the pollinator. Still others have theorized that swarms of tiny gnats do the job. More research is required.

But the coolest thing about this fascinating plant? Because of its strangely late pollination, there isn’t time for the seeds to ripen in the same year the flowers open. It takes the whole next summer for seeds to slowly ripen in their pod. Then, just as the flowers start blooming again in the freezing cold, the pod explodes throwing ripe seeds 10 to 20 feet away, where they will rest until spring weather is warm enough for germination. It’s a risky reproduction strategy, but it seems to work well for this native plant.

Witch-hazel is an easy choice for smaller properties. As a multi-trunked tree or shrub, it rarely exceeds 20 feet in height. It is an understory plant, so it does well in part shade under mature trees, but is also happy with more sun. It is winter-hardy in Zones 3 to 8, and is not fussy about soil, but average moisture and a covering of leaf litter throughout the season is recommended. No special care is required and Witch-hazel rarely needs pruning. In summer, it is an open, airy plant with medium green leaves, but in fall, the leaves turn apricot gold before dropping just as the crazy flowers start to open. The flower show typically lasts a month or more.

Lately, we’ve seen nurseries offering non-native hybrids of Witch-hazel for sale. These varieties with orange or red flowers are recent introductions of hybridized Asian species, so their value to our native wildlife and potential for invasiveness are unknown. Our view is that it’s always safer to go with species that evolved in our region.

Hamemelis virginiana, our native Witch-hazel, is a garden-worthy plant that brings late-season interest to suburban landscapes. Try it against a background of evergreens or with berry- producing shrubs. On a cold winter’s day, you won’t be sorry.