The evergreen Rhododendron is an iconic shrub in the Eastern US. Indeed, it is hard to imagine our landscapes without it. Its big shiny leaves and glorious spring flowers make it a year-round favorite.

The two best-known native evergreen “rhodies” in the Eastern US are Catawba (Rhododendron catawbiense) and Rosebay or Great Laurel (Rhododendron maximum). Catawba is the rhodie we see most often in suburban landscapes, either the native species with pinkish-purple flowers, or one of the many hybrids with non-native species, such as ‘Roseum Elegans’ and ‘English Roseum.’ The shrubs you see blooming in mid-spring with big showy flowers ranging in colors from pale pink to hot fuchsia usually are Catawba hybrids.

Rhododendron maximum is larger, with big, slightly floppy leaves and pinkish-to-white flowers that bloom a few weeks later than the Catawbas. While Catawba shrubs typically reach 8 to 10 feet tall and wide, Rosebay can top out at 15 to 25 feet with an equally wide spread.

Though Catawba’s original range was in the Southeast, from Virginia to Georgia, it performs very well in Zones 5 to 8, so it is a good choice for gardens in New York and the mid-Atlantic region. Rosebay Rhododendron is native from Maine all the way to the mountains of Tennessee, and hardy in Northeastern winters through Zone 4. Both shrubs prefer rich acidic soil and moist-to-dry conditions in sun to part shade. Protection from very hot afternoon sun and supplemental water during prolonged drought is recommended.

Evergreen Rhododendrons in the wild can form massive, impenetrable thickets that shade out competing plants, including trees. In the Appalachians, Rhododendron thickets viewed from a distance are so dense and treeless that they make the hillsides appear smooth. Locals call them Rhododendron “slicks” or “balds” because they look almost like lawns on distant hills. Up close, however, the reality has earned them the name rhododendron or laurel “hells.” Hikers, hunters, and their dogs, have been lost for days, unable to find their way out of the tangle of branches — too tall to see over, and too dense to see through. But Rhododendron thickets have also served as a refuge for both humans and animals.

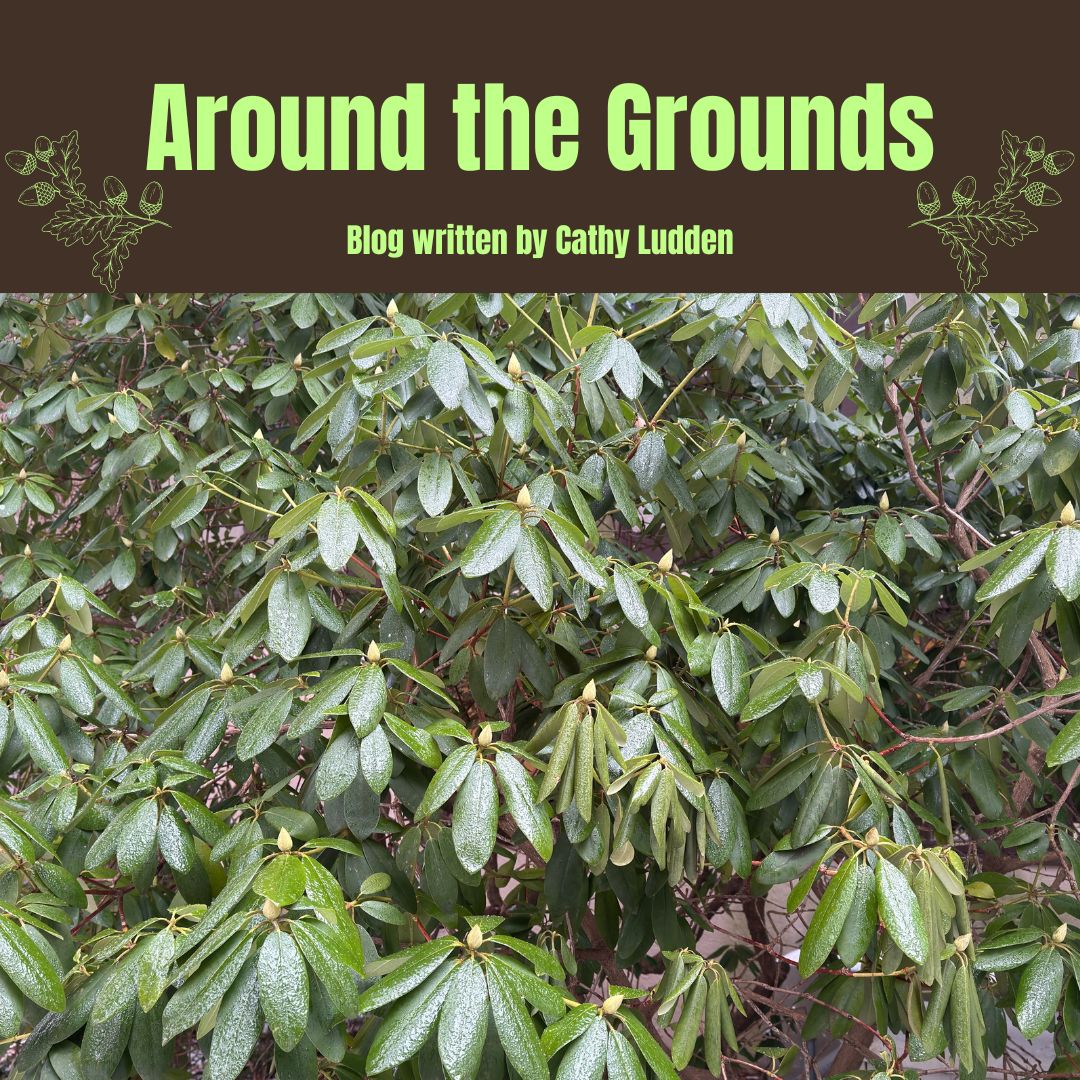

a Rhododendron thicket

In 1838, under authority of the Indian Removal Act, the United States government forced more than 16,000 Cherokee people to leave their homelands in Tennessee, Alabama, North Carolina, and Georgia, marching them to Oklahoma along the tragic “Trail of Tears.” The Cherokee people of Nantahala in North Carolina, however, resisted the round-up by government troops and fled to “laurel hells” in the Nantahala River Gorge. Led by Oochella, “a man who made himself somewhat notorious by threats of resistance,” the Nantahala fugitives evaded the military by hiding in what one contemporary journalist described as “the most gloomy thicket imaginable… Even at noonday, it is impossible to look into it more than a half dozen yards, and…no white man is yet known to have mustered enough courage to explore the jungle.” Eventually, after a number of lethal skirmishes, government troops granted amnesty to the remaining fugitives and withdrew. Oochella and his followers joined the Qualla Cherokees and formed a community that survived as the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

In modern landscapes, the dense evergreen cover of Rhododendrons makes these shrubs ideal as privacy screens. Instead of a tight row of clipped Arborvitae or a taxus hedge, a screen of Rhododendron provides much greater visual interest, as well as critical habitat for pollinators and birds. In spring, the enormous flower clusters provide nectar and pollen for bees and butterflies, and throughout the year, evergreen Rhododendrons are safe hiding places for birds.

It is no exaggeration to say that evergreen Rhododendrons planted next to your house will give you bird-watching opportunities in every season. Even on the coldest days of winter, when freezing temps cause Rhododendron leaves to curl tight to avoid damage, winter birds will seek refuge in the Rhododendron.

Each of these photos was taken from a window looking into a Rhododendron:

Rhodies grow fairly fast, are easy to care for, and provide critical habitat. Deer will eat Rhododendron leaves if they can reach them, but only if there is nothing else available. The leaves are actually toxic to most mammals, including horses, sheep, and cattle, so it is a last choice for deer, too. Fencing at the base of the shrub, especially when it is young, helps protect it until it grows out of reach.

For more information about evergreen Rhododendrons, including their strange

ability to tell you the outdoor temperature, click here.