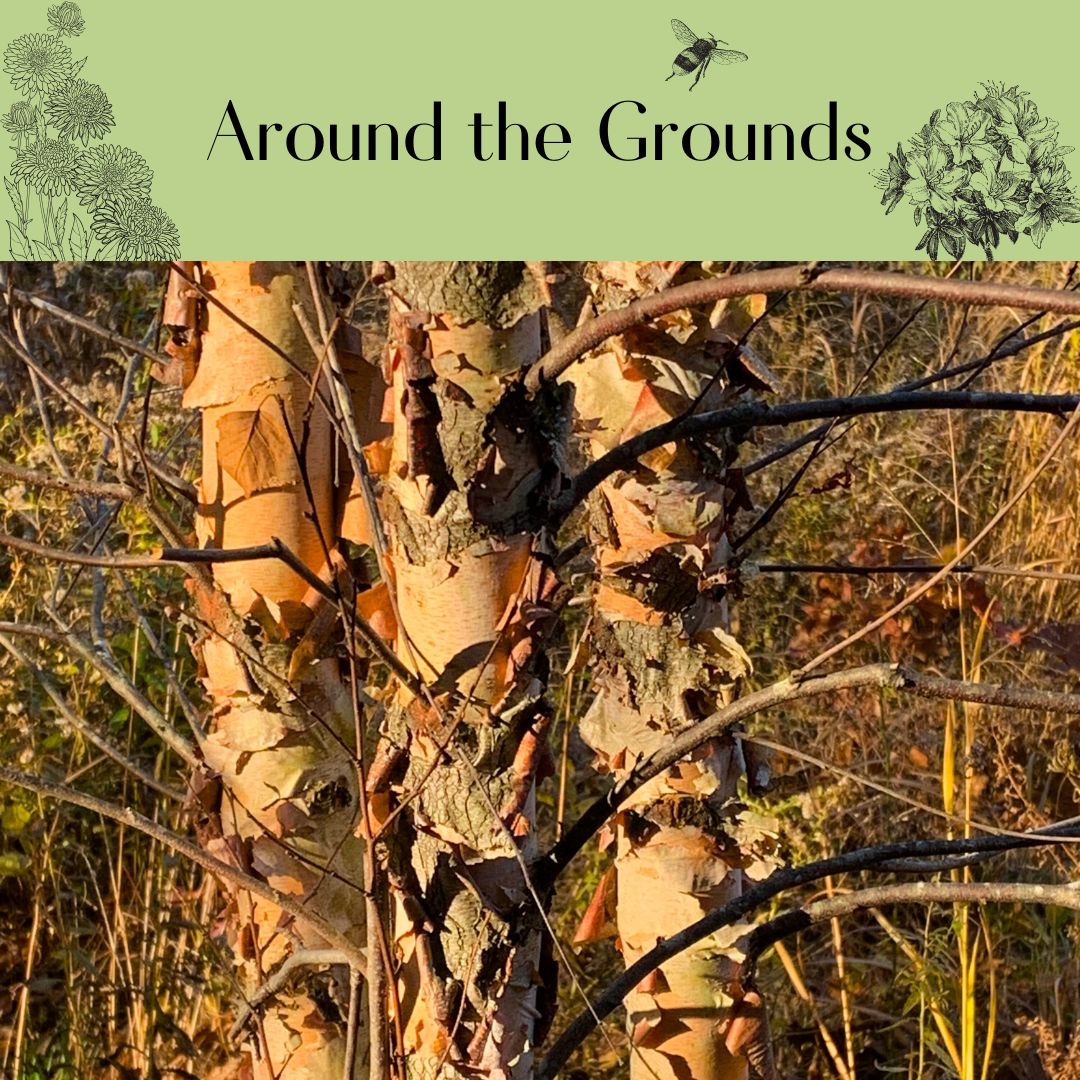

If you were a hungry bird looking for a high-protein snack in mid-winter, where would you go to find some tasty insects? And if you are a human desperate for something interesting to look at in the mid-winter landscape, what would you like to see out your window or along a path? To answer both questions, take a look at the gorgeous bark of our native River Birch (Betula nigra).

River Birch is a great tree for landscapes in our area. As the name implies, its native habitat is stream-side or near a pond. But it is perfectly happy in our acidic soil with average moisture. We have it planted next to the Meadow at the Nature Center, without any irrigation at all, and it is doing fine. It is also perfect in an area that floods occasionally, as long as the soil dries out in a few days, and there is plenty of sun.

River Birch can be a single-trunk tree, but it is more commonly multi-trunked, which adds some interesting variety to residential plantings. It is fast growing – over two feet per year – and can reach 50 to 70 feet ultimately. It does not pose a risk to houses or other structures, but it will drop lots of small twigs after a wind storm. River Birch has small glossy leaves that move lightly in the breeze and provided dappled shade. Fall color is golden yellow and lasts for weeks.

Birch trees are one of the most valuable host species for butterflies and moths, providing the critical food source for 413 species of Lepidoptera (butterfly and moth family). And that means birds will flock to your River Birch all summer to find caterpillars to feed their chicks. A birch grove is a bird sanctuary all summer with lots of food and hiding places. And in the winter, woodpeckers, nuthatches, chickadees, and many other birds will hunt in the millions of folds and crevices in the bark for over-wintering insects.

As River Birch matures, the bark becomes less flaky on the lower trunks, but the upper branches retain that cinnamon color and peeling texture. Don’t underestimate the ultimate size when you plant River Birch. After 20 years or so, each trunk can reach over a foot in diameter, so a multi-trunked tree will need some room.

But what a pleasure that bark is in the winter landscape!

This blog is authored weekly by Cathy Ludden, conservationist and native plant educator; and Board Member, Greenburgh Nature Center. Follow Cathy on Instagram for more photos and gardening tips @cathyludden.

“a food pantry for birds” – what great description!

Lynne R

?

Always interesting, Cathy! I want to find a space for one or more on our property.

Thanks, Nancy! Because they are typically multi-trunked, even one creates the impression of a stand of trees. Something interesting to look at when all the leaves are down, too.