There is a fascinating little plant, just emerging now in the early days of spring, that is a marvel of evolution. It is also one of our favorite native ground covers for shade.

Asarum canadense, Wild Ginger, is native to shady forests from Northern Canada all the way south to Georgia and west to the Dakotas. It has beautiful leaves that grow in pairs like rounded hearts. It grows very close to the ground, never more than 3 or 4 inches high, and it forms lush mats that densely cover a slowly expanding area. It spreads about 6 inches in each direction every year.

Underneath the pretty leaves, Wild Ginger hides its secret flowers. There are lots of flowers, but you have to get down low and push aside the leaves to find them. The flower stems and leaf stalks (petioles) are covered with downy hairs that give them a furry appearance. The flowers are purplish brown, with 3 pointed petals that open to a little cup where the stamens with pollen are hidden.

Botanists believe that Wild Ginger evolved with its flowers right next to the ground to attract early-season flies as pollinators. Flies emerge from the ground looking for carrion. They promptly find the brownish flowers of Wild Ginger right on the ground and crawl inside. There they hide from rain and the cold nights of early spring, snuggling into the cup-like flowers and accidentally collecting pollen on their bodies that will be transferred to the next flower they visit.

Seeds develop in the pollinated flowers, and when they ripen, they are discovered by ants. The seeds have oily little appendages that are nutritious and delicious to ants who carry them off to their colonies. The ants eat the oily part, but abandon the seeds to germinate. Not only are the seeds protected this way from seed-eating animals, but they are effectively planted by the ants.

Wild Ginger is in the same botanical family, Aristolochiacea, as our native Pipevine, the host plant for the gorgeous Pipevine Swallowtail butterfly, and many experts believe that Wild Ginger is an alternate host plant for the Pipevine Swallowtail caterpillar.

Wild ginger does indeed taste like ginger, though eating much of it may be toxic and is not recommended. Indigenous Americans dried the tubers and ground them as a spice. Early colonists boiled the tubers with sugar water, making something like candied ginger and then used the cooking liquid as a syrup. Both groups used the plant as a poultice to treat wounds, and modern research has confirmed the presence of two antibiotic compounds in the plant.

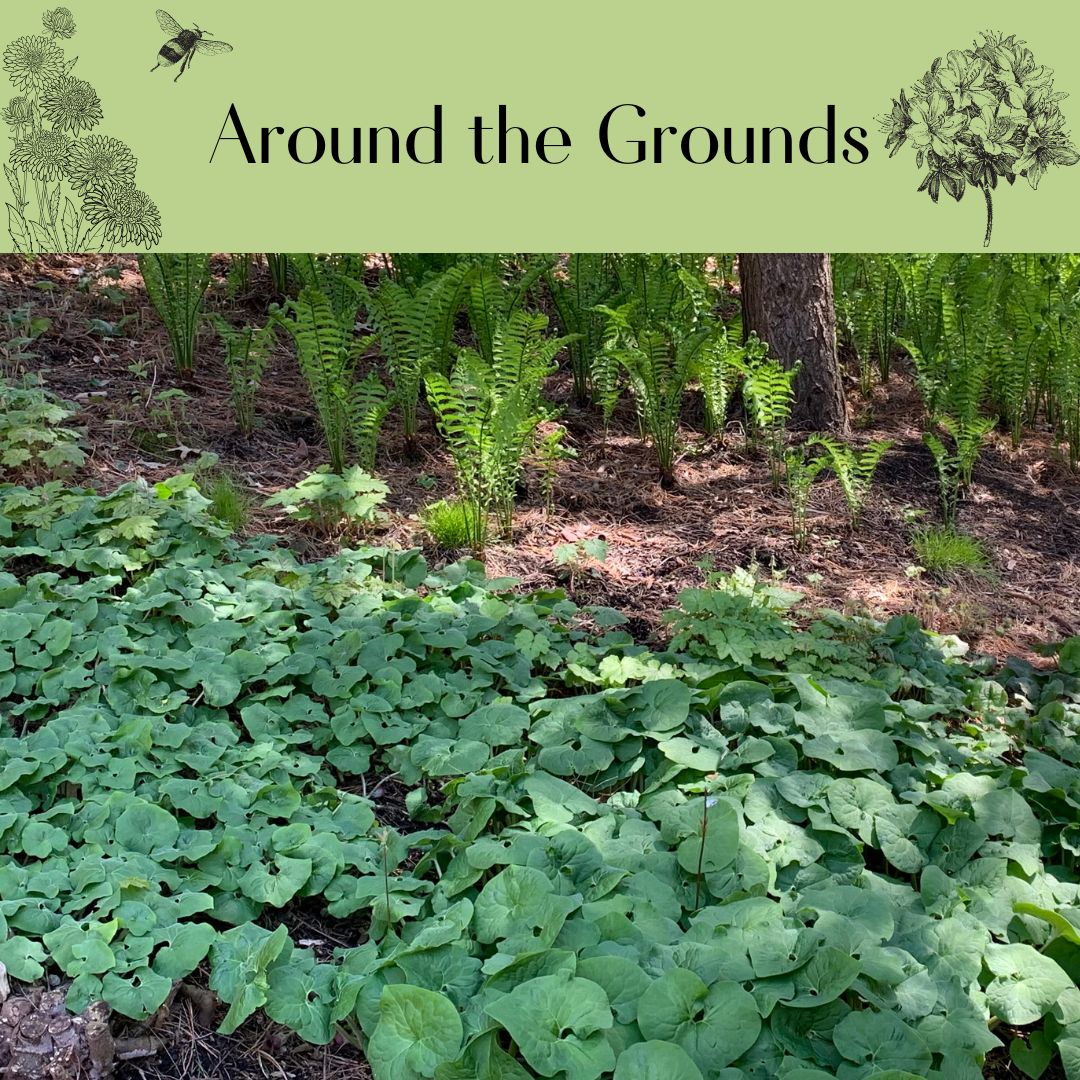

Today, we know Asarum canadense best as a fantastic shade ground cover. It preserves soil moisture and suppresses weeds all summer. It is deciduous, so it uncovers bare ground for the winter, which benefits ground-nesting native bees, flies, and beetles. As a garden plant, it is absolutely gorgeous in combination with ferns and shade-loving grasses. It is ideal under trees and shrubs, as well as in wooded areas, and eliminates the need for mulch. Deer completely ignore it.

So, this amazing plant evolved offering shelter to the little flies that pollinate it, feeding the ants that protect and distribute its seeds, and hosting caterpillars that turn into beautiful butterflies that pollinate other plants. It healed the wounds and spiced the food of the earliest humans on this continent. It is beautiful, and perfectly adapted to our climate. It is not difficult to grow, and it does exactly what we want our ground covers to do. It belongs here in every sense of the word. Wild Ginger is a perfect example of the benefits of native plants.

Why, then, do we see so much pachysandra, ivy, vinca, wintercreeper, and other non-native ground covers escaping suburban yards to infest our woodlands, suppress native plants, diminish food sources, and even pull down our trees? Why would we choose those imported plants when the perfect plant always has been right here?

We can’t help but wonder.

What a delightful article you’ve written Cathy. This is probably the most compelling champion writing about the humble wild ginger. One of my favorites and a gorgeous shade lover. It’s happily thriving in what was a “troublesome shade bed” along with moss phlox, fringed bleeding heart, foamflower, stonecrop, Virginia waterleaf and Christmas ferns. It’s one of my favorite gardens at our little urban pocket park.

Thank you for the kind words, Dawn. The more we learn about the relationships between these amazing native plants and their ecosystem partners, the more beautiful they become, I think. I can no longer separate how a garden looks from what it does ecologically. “Pretty is as pretty does,” right?

What a wonderful blog. We may have to get rid of our vinca after reading this but it does do a good job of holding the soil on some of our slopes. Any other native recommendations for that purpose?

We loved your garden tour yesterday but as we left your property through the front right border we noticed a multi stemmed tree with smooth reddish bark but didn’t have a chance to ask the name? What is it?

Thanks, Alan! That is a paper bark maple. It’s not native, so I didn’t highlight it. I planted it many years ago after seeing a spectacular specimen at the New York Botanical Garden. It really is a beauty.

Thanks Cathy.

This is the year I start eliminating some pachysandra, and this does seem like a great solution. Thank you Cathy!

Lynne

Hi Cathy,

Another great blog and it makes me want to banish my pachysandra and replace it with wild ginger. Thank you again for helping me learn a little more each week.

Jim

If you go to the trouble of removing pachysandra and planting native ground covers, the pay-off really is worth it. First, your own garden will be prettier and more interesting for you, and second you will benefit our local ecosystem. Win-win!