No, not that kind!

The “good weeds” we feature here are special native plants that pop up spontaneously in our gardens, lawns, and roadsides. They may be “weeds,” but they are also beautiful and important to local birds and pollinators. So, before deciding to get rid of them, you might pause, consider them a gift from nature, and allow them a place in your garden. After all, what is the difference between a “weed” and a “wildflower”? If a native wildflower appears in your garden, is it a nuisance or a happy accident?

Native plants (the plants that evolved in a particular ecosystem without human intervention) may — and should — propagate themselves in their natural habitat along with the other plants, insects, and animals that evolved there. When these native plants “volunteer” in our yards, especially in the right spot, simply allowing them to stay may be a good choice. And because they are better adapted to their native area, they may out-perform the plants we buy that need special handling, fertilizer, and extra water.

Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis) is a good example. Native to most of North America, Jewelweed is an annual, but it can return each year because it freely self-sows, dropping seeds that will sprout the next season. It prefers rich, moist soil and part shade, but can appear in sun or shade, in soggy areas, and even in heavy clay. The Latin name Impatiens and “Touch-me-not,” another common name for the plant, both refer to the explosive way its seed capsules burst, throwing seed all around the mature plants.

Jewelweed starts blooming in late summer and continues well into fall. The flower is shaped like a cornucopia, and its nectar provides critical energy for migrating hummingbirds and monarchs, as well as late-season bumblebees. The plants require no care whatsoever, and the bright orange flowers light up the fall landscape.

If Jewelweed appears in your garden where you don’t want it, it is easy to pull. But it makes a great show in spots where you can leave it standing.

Another wildflower that frequently volunteers in shady areas is White Wood Aster (Eurybia divaricata). Native to the Eastern US, it blooms earlier than most asters, beginning in late summer. Native bees love it, and birds eat the seeds all winter. It is not an aggressive spreader, so you can relax if it pops up in your yard. It looks beautiful scattered around under trees and shrubs. You can even find White Wood Aster sold in nurseries if you want to plant it, and it is a great choice for dry shady spots – even where there are deer.

If you’re lucky, a very similar-looking wildflower may also appear in shady areas in the fall. Common Blue Wood Aster (Symphyotrichum cordifolium) is native to most of Eastern and Central North America and found along forest edges and open areas, as well as in urban and suburban gardens. Its flowers are pale blue and it grows taller than White Wood Aster, typically 2 to 4 feet. We find it along woodland paths and even street-side where deer seem to ignore it, as they do White Wood Aster.

If you live in the Central or Eastern US, you’ve probably seen White Snakeroot (Ageratina altissima) popping up in various places. Blooming in early fall, White Snakeroot attracts a wide range of pollinators to its nectar-rich flowers. Bees, butterflies, moths, and even spiders preying on the nectar-hunters, all visit the clusters of tiny flowers produced by these native plants.

White Snakeroot has an interesting history. At one time, it was believed – erroneously — that the roots could treat snakebite. In fact, the entire plant is toxic to mammals, so deer avoid it entirely. Early American settlers discovered that if cows consume White Snakeroot, their milk becomes poisonous. Abraham Lincoln’s mother is said to have died from “milk poisoning,” as it was called then.

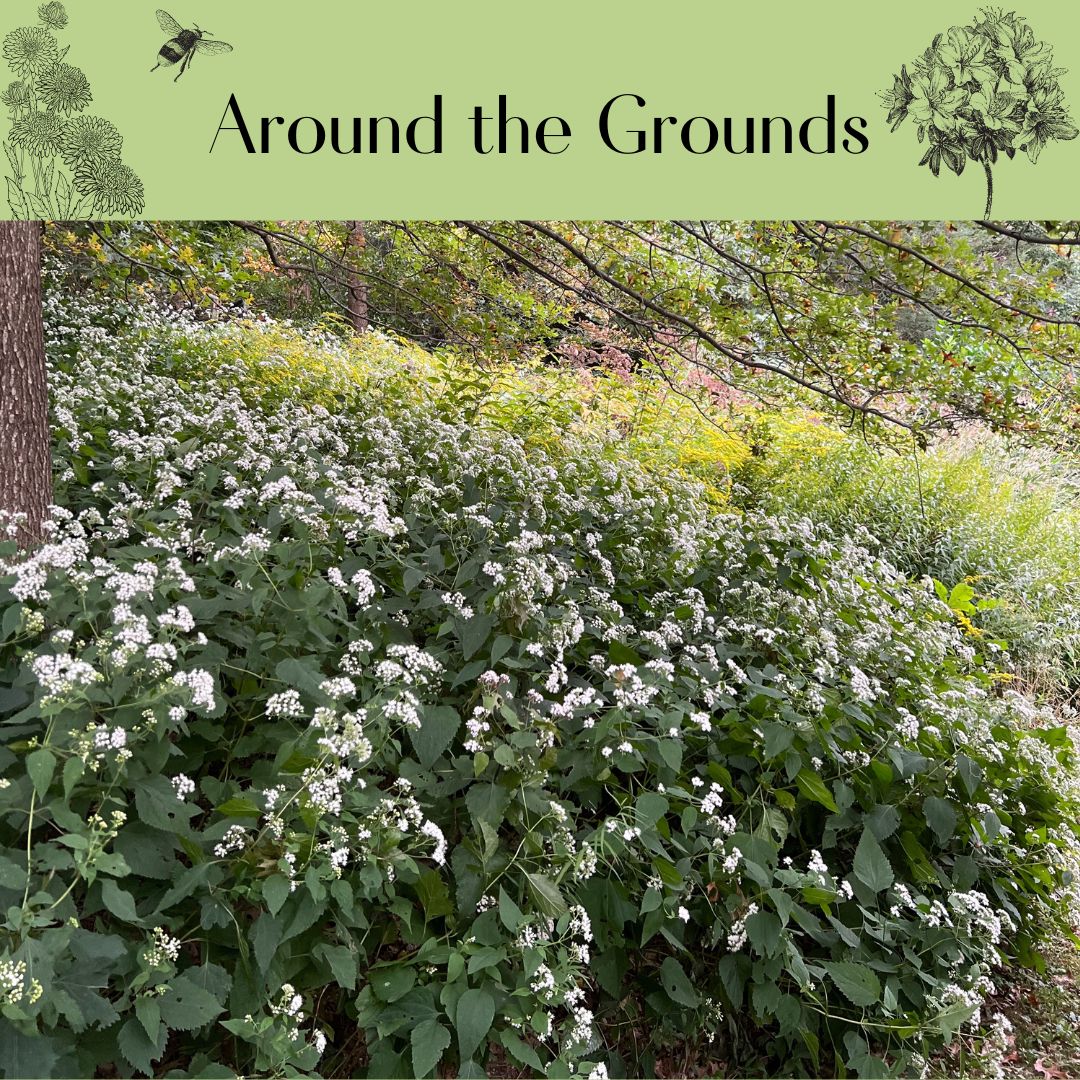

In the landscape, however, White Snakeroot is dazzling. The plants grow up to 3 feet tall, and the flowers are brilliant white against dark green leaves. Snakeroot is spectacular massed in shade where it can be a very effective groundcover. It does well in part sun also, and in either dry or moist soil. It is an aggressive spreader and can be challenging to control in smaller gardens. Its seeds are produced in large numbers and wind born, but it also spreads by rhizomes.

If White Snakeroot appears in an area where there is only ivy or pachysandra, or in dry shade under old trees, or on a tough embankment where other plants struggle, you may just want to leave it alone and let nature take its course!

All of these are wonderful. Pulling out my lawn and planting a native pollinator garden is the most rewarding yard project my husband and I have ever undertaken.

So happy to hear that! Changing behavior to make a more healthy ecosystem is our top priority. You made my day!

I no longer weed so many of these plants now in bloom around my garden. There were many blooming yesterday throughout NYBG’s Native Garden!

Ooh, I should get over there — fall is a great time in the native garden!

Thanks to you I have a greater appreciation for these natives and will leave them to enjoy. Great information.

That’s great! If they become overwhelming (cough, snakeroot) you can always deadhead them to reduce self-seeding.

very cool! I love the way a lot of these native wildflowers look! 🙂

Very helpful, interesting information, as usual!