Meadows change. All landscapes change, of course, even the most formal manicured gardens. But native plant meadows are wilder, less predictable. Nature has a freer hand where plants are allowed and expected to reproduce naturally, and where humans impose less control over conditions. In each season since the initial planting of our native Meadow (see last week’s blog post here), we have been surprised, sometimes frustrated, and always fascinated by the changes we see. Our challenge is to accept as many of nature’s changes as we can, while preserving the value of the Meadow for nature itself.

In the Northeastern US, which was once almost entirely forest, naturally-occurring meadows are typically “successional.” They occur when a storm or fire opens a spot in the forest and more sunlight allows grasses and wildflowers to emerge. Eventually, woody shrubs and tree seedlings settle in, grow taller, cast shade, and the forest returns. Unfortunately, in modern times, any newly opened ground is immediately colonized by invasive species, plants from other parts of the world that out-compete native plants because they have no natural insect or animal controls here.

So, maintaining a designed meadow in the Northeastern US requires effort to prevent invasive plants or forest from claiming the space. The incredible value of a native meadow as habitat for insects, birds, reptiles, and mammals makes that effort totally worthwhile.

We begin each year in the Meadow by mowing to prevent tree seedlings from developing, and to allow sun and water to reach new growth. The timing of mowing is important. We need to wait for over-wintering insects, including native bees and caterpillars, to emerge from their hiding places in leaves and hollow stems, usually in late March or early April. The Meadow is cut to the ground, leaving plant debris in place to add nutrition to the soil and to protect emerging growth from late frosts.

Spring mowing also allows us to check the Butterfly Arbor and the trees in the Oak Circle for any winter damage. And it’s a good time to look for and remove invasive species before they can hide among the native plants.

A few weeks after mowing, when the first spring flowers emerge, we see that the Meadow has changed again. Each year there are surprises, and occasional disappointments, as plants appear and disappear. We are delighted when native plants volunteer in places they were never planted – a true indication of a healthy landscape! And, sometimes, we notice that flowers we love have disappeared as they reach the end of their life expectancies, or lose ground to stronger plants.

Photo: Travis Brady

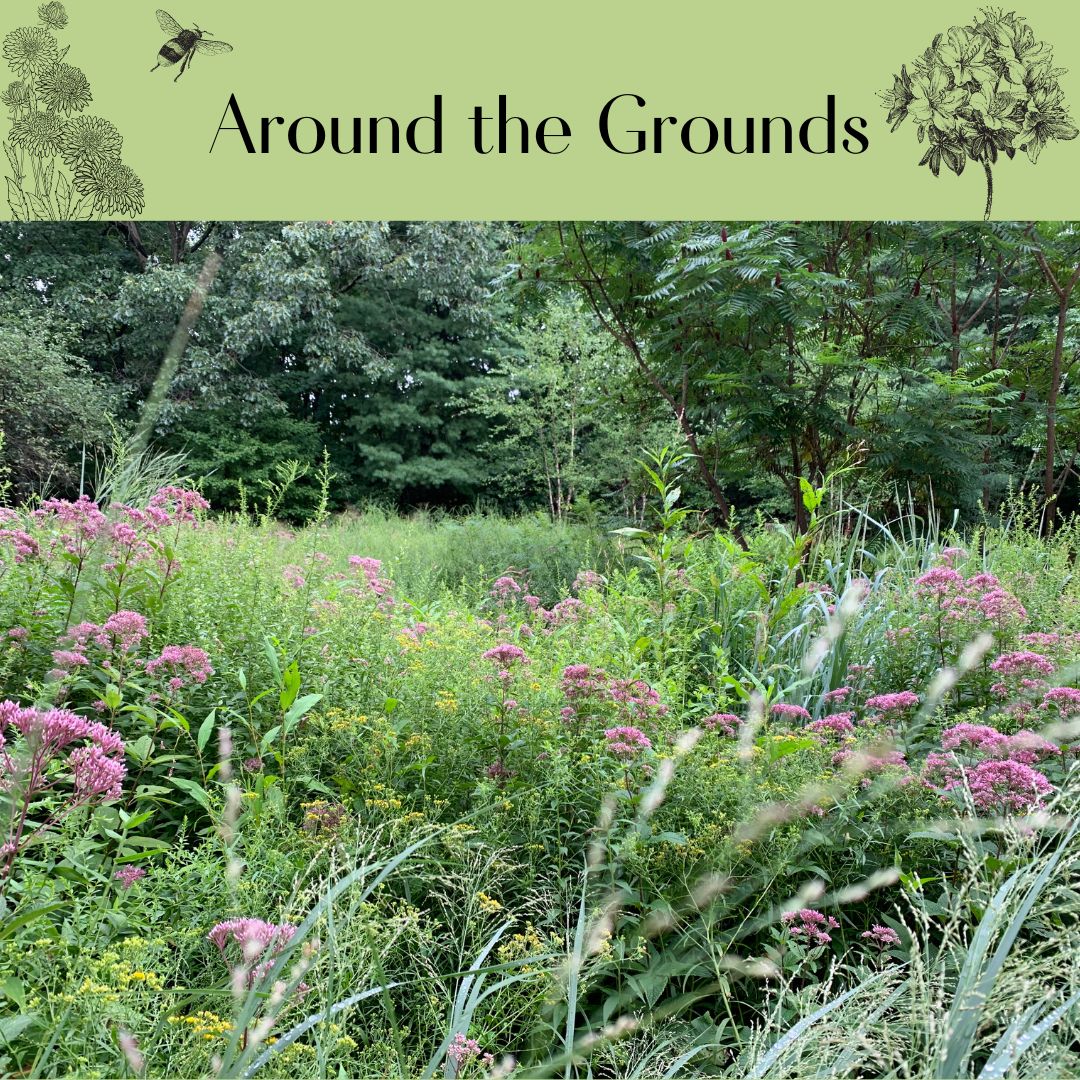

By June, the Meadow is in full bloom. Coreopsis, Penstemon, Baptisia, and many other flowers greet visitors — including butterflies, bees, and countless other pollinators!

Throughout the summer, the Meadow continues to change – not just seasonal changes, but changes in plant populations. Years after the original seeding, plants have appeared and bloomed for the first time as slow-growing seeds finally matured. And the number and location of plants in the Meadow changes every year.

Throughout the growing season, some weeding is necessary to keep invasive plants out of the Meadow. Even some native plants are too aggressive to leave uncontrolled, or they would soon dominate. We make careful edits, avoiding use of herbicide, and quickly fill in weeded areas with container-grown native plants.

Autumn is the most dramatic season in the Meadow. Late-blooming flowers and grasses change the scene daily with a profusion of color. Seed pods from faded flowers attract songbirds in large numbers, and bees scramble to stock up for winter.

Photo: Travis Brady

Meadow plants are left standing all winter to provide seeds for birds, cover for animals, and winter hiding places for insects. There is a lesson here for all of us as home gardeners: a little mess, a little bit of wild in the landscape, can be as beautiful as it is beneficial for living things.

As the light changes with the seasons, the Meadow changes, too. It really is a different place each time we visit!

Incredible Blog!

Thank you Cathy.

Thank you, Rex.

It is better to remove the plant debris after mowing. This will create more biodiversity ( look up terrestrial eutrophication) Without haying/fire/grazing you will get a mulch and nutrient build up that will favor invasives and rhizomatous plants like beebalms, goldenrods, joe pye weeds or worse: invasive vines, japanese knotweed and mugwort. etc. The removal of mulch and nutrients is the key factor for good meadow management.

I do wish we could burn!

I’m interested in this issue from the point of view of a garden designer, who tries to advise clients re ongoing management … I have wondered about the annual buildup of organic material, whether it would trend the soil towards more richness and cause certain plants to flop, etc. Not only that but there are times one needs to avoid accumulation of organic matter . It was mind-blowing to me when I realized that the High Line needs to remove everything at cutback, due to structural limitations, bed depth, etc. Of COURSE! I have designed a few rain gardens, and I need to avoid “filling in” the water depression over time, leave the space for water. (Although in smaller residential rain garden systems, I find once plants establish, and soil below begins to open up, there’s much quicker rain infiltration anyway.) Not sure what to do… remove debris + compost elsewhere for use where needed? Avoid high bio-mass herbaceous plants in favor of… what?… woody plants?

The advice we’ve received from meadow consultants is to leave most of the last season’s material in place. Burning every few years would be optimal, but not possible here. We do have some big switch grass clumps, and some of the broader leafed types create heavy masses that we take to the compost. By spring, most of the forbs have broken down pretty well, and leaving them in place has worked so far. Our mower chops them into fairly fine pieces. Our meadow is 7 years old and we haven’t seen a problematic build-up of organic matter yet. We avoid open and disturbed soil because of the invasives pressure from surrounding areas. Leaving dried plant material in place helps prevent weeds from seeding in. We cut back some of the more aggressive plants (Canada goldenrod) in late summer before they can go to seed, and we may do a bit more of that sort of management to keep diversity. I am told that there is no one-size-fits all answer to your question, but that’s what has worked for us so far.

Every sentence is a gem of expert information! The closeups by Travis are a nice addition.

Travis takes amazing photos! Some of my very favorite meadow photos are his.