Are you frustrated with deer destroying your arborvitae? Are you sick of seeing your curbside hedge poisoned by road salt? Are you fertilizing your boxwood or yew hedge to make it grow even though you end up trimming off the new growth every year? Are you embarrassed to learn your barberry, privet, burning bush, or forsythia hedge is invasive and spreading into natural areas provoking disapproval from the neighbors?

Well, friends, we’ve got good news for you! How about a hedge that is deer tolerant, salt tolerant, drought and flood tolerant, doesn’t need pruning, and even makes its own fertilizer? This wonderful shrub grows in sand, clay, or rocky soil and survives mostly on sunshine. It’s beautiful, fragrant, supports wildlife, and provides you with a long-lived privacy screen.

Northern Bayberry (Myrica or Morella pensylvanica) is a fantastic plant that is inexplicably under-used in suburban landscapes. It is native to the Atlantic coast from Newfoundland to North Carolina and as far inland as Ohio. Its natural habitats include seaside dunes, pine barrens, dry forests, rocky slopes, and even bog and swamp edges, which explains its versatility in gardens. It is hardy in zones 3 to 7, and semi-evergreen in the warmer part of that range.

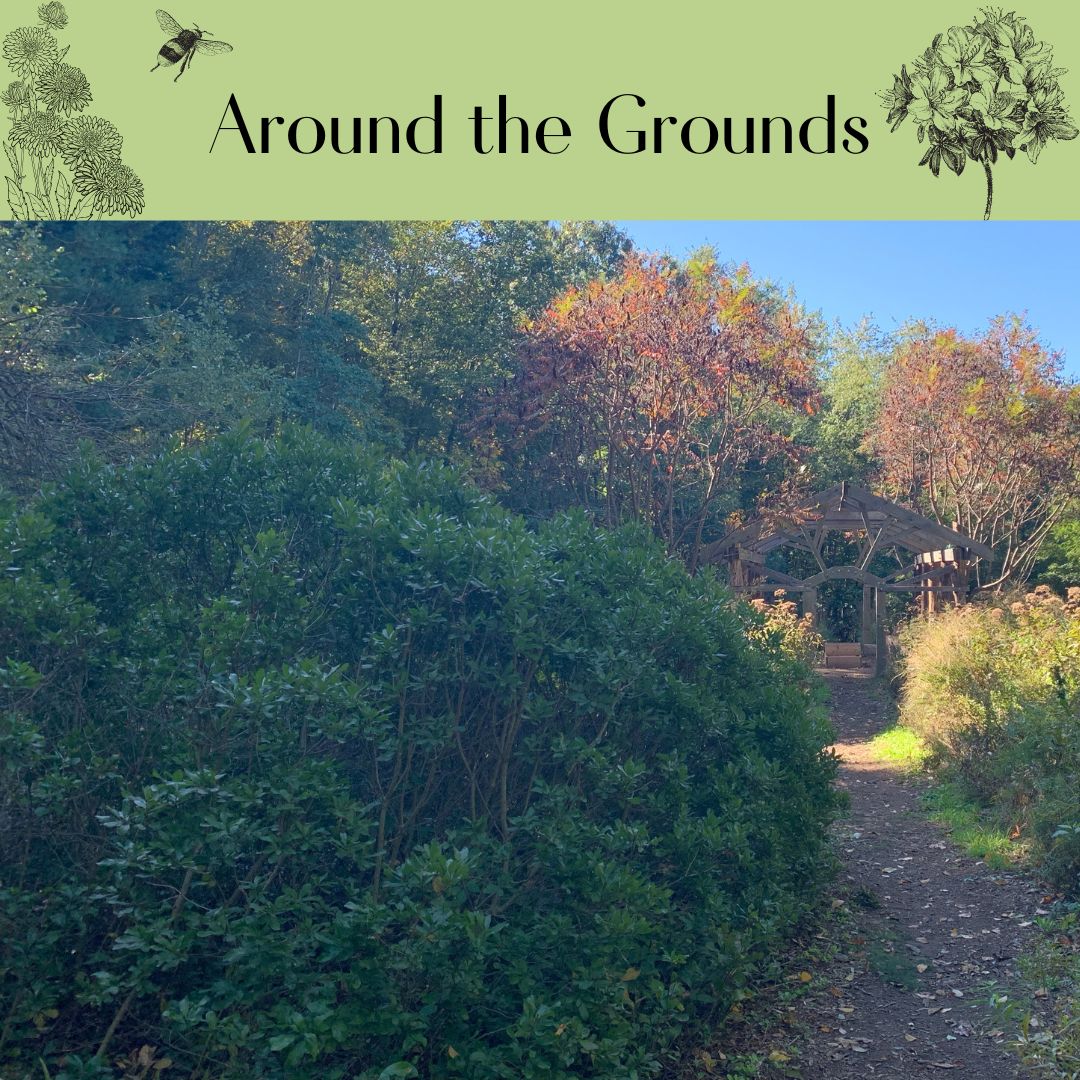

Bayberry naturally takes the form of a dense rounded shrub, 5 to 10 feet tall and wide, with glossy fragrant leaves and gray-green scented berries. It can be used as a specimen or foundation plant, but it is particularly attractive massed as a privacy screen or informal hedge. It does not thin out at the bottom with age or become leggy. The shrub expands very slowly by extending suckers out from its base, but does not try to take over. Once it reaches its full height, it will retain its shape and survive for many years. We suspect the Bayberry hedge along the Meadow path at the Nature Center has been there for close to 50 years.

As the name suggests, Bayberry produces interesting berries that cling close to the stems over the summer. The shrub is naturally dioecious, meaning male and female plants are necessary for berry production. But modern horticulturists have managed to combine at least some male and female flowers on single plants for guaranteed berries. Planting both male and female plants, as you would in a hedge, assures maximum berry production.

The berries are a magnet for birds, including chickadees, mockingbirds, blue jays, cedar waxwings, cardinals, robins, catbirds, and the beautiful yellow-rumped warbler. Even after Bayberry drops its leaves in the winter, the dense branches form a thicket that shelters birds from predators. At least two species of caterpillars also rely on Northern Bayberry as a larval host, including the red-banded hairstreak butterfly and the Columbia silk moth.

Northern Bayberry belongs to that interesting group of plants that utilize specialized bacteria to fix nitrogen in the soil. It is amazing to see Bayberry growing lush and green in nothing but sand because it is essentially manufacturing its own nutrients from air and sunlight. In your garden, the nitrogen provided by Bayberry can enrich the soil for other plants as well.

Northern Bayberry does best in full sun. It is relatively slow-growing, so pruning is not necessary, but it can be pruned for a more formal effect.

Photo: Carolyn Summers

Photo: Carolyn Summers

American colonists recognized the value of Northern Bayberry for making scented candles. The berries were boiled until the waxy outer coating floated to the top. After cooling and re-melting, the wax could be poured into molds or used for dipping tapers. The wax burns clean with a lovely herbal scent, and is still used for that purpose. The aromatic leaves have been used for their fragrance and various medicinal purposes as well. It is the aromatic quality of Bayberry leaves that makes the shrub so unattractive to deer.

Though American settlers appreciated Northern Bayberry and planted it in their gardens as early as the 1700’s, the introduction of exotic ornamental plants in recent times seems to have diminished its popularity. That should change. If you are frustrated with the failings of over-used hedge plants, consider Northern Bayberry. It really is a better hedge.

Had no idea there was something like this, this is great!

Thank you! I hope you can use it!

Thank you, Lynne. I have been thinking I may even replace some native inkberries with bayberry. The inkberry is evergreen and lovely, but tends to get bigger faster and can get leggy after a few years. And I just really love the fragrance of the bayberry.

Hmmmm … another interesting selection, of which I knew little …. until today.

Thank you Cathy!