Spring is approaching! Garden and seed catalogues are arriving in the mail. Nurseries and big box stores will soon begin displaying thousands of plants for our home gardens.

As we plan to beautify our yards, it’s easy to be seduced by photos of gorgeous flowers and promises of carefree shrubs. But beware: many of these plants are not as advertised! It pays for avoid common mistakes now to prevent later problems that can cost you dearly.

The biggest mistake, both for nature and your wallet, is buying invasive plants. And it’s too easy to do! Many of the most common and familiar yard plants are actually invasive species. And most of them are still being sold across the country every day!

The term “invasive” applies to plants from other continents that have no natural controls in North America (nothing here eats them!), and they are so successful at reproducing themselves that they spread unchecked causing environmental and economic harm. Invasive plants cost the US – individual property owners, corporations, non-profits, and all levels of government combined – an estimated $142 billion annually! Because invasive plants out-compete native plants, they take over forests, grasslands, wetlands, roadsides, parks, and residential areas, eliminating food and other resources for wildlife, as well as pulling down power lines, trees, fences, and damaging building siding and exterior finishes. Fighting invasive plants is frustrating and very expensive.

There are at least 5000 plant species currently identified as invasive in the US, and over 2/3 of them were introduced to this continent not for food, medicine, or commercial value, but simply because somebody thought they made pretty garden plants. Many states, including New York, have begun to regulate the sale or marketing of a few species of invasive plants. But the power of the nursery industry, and the popularity of many invasive plants with gardeners, has prevented more effective legal controls. Nurseries and mail-order houses still sell hundreds of invasive species. In fact, the nursery industry is the primary pathway for invasive plant introduction. Ultimately, though, it’s up to homeowners and gardeners to refuse to buy these plants.

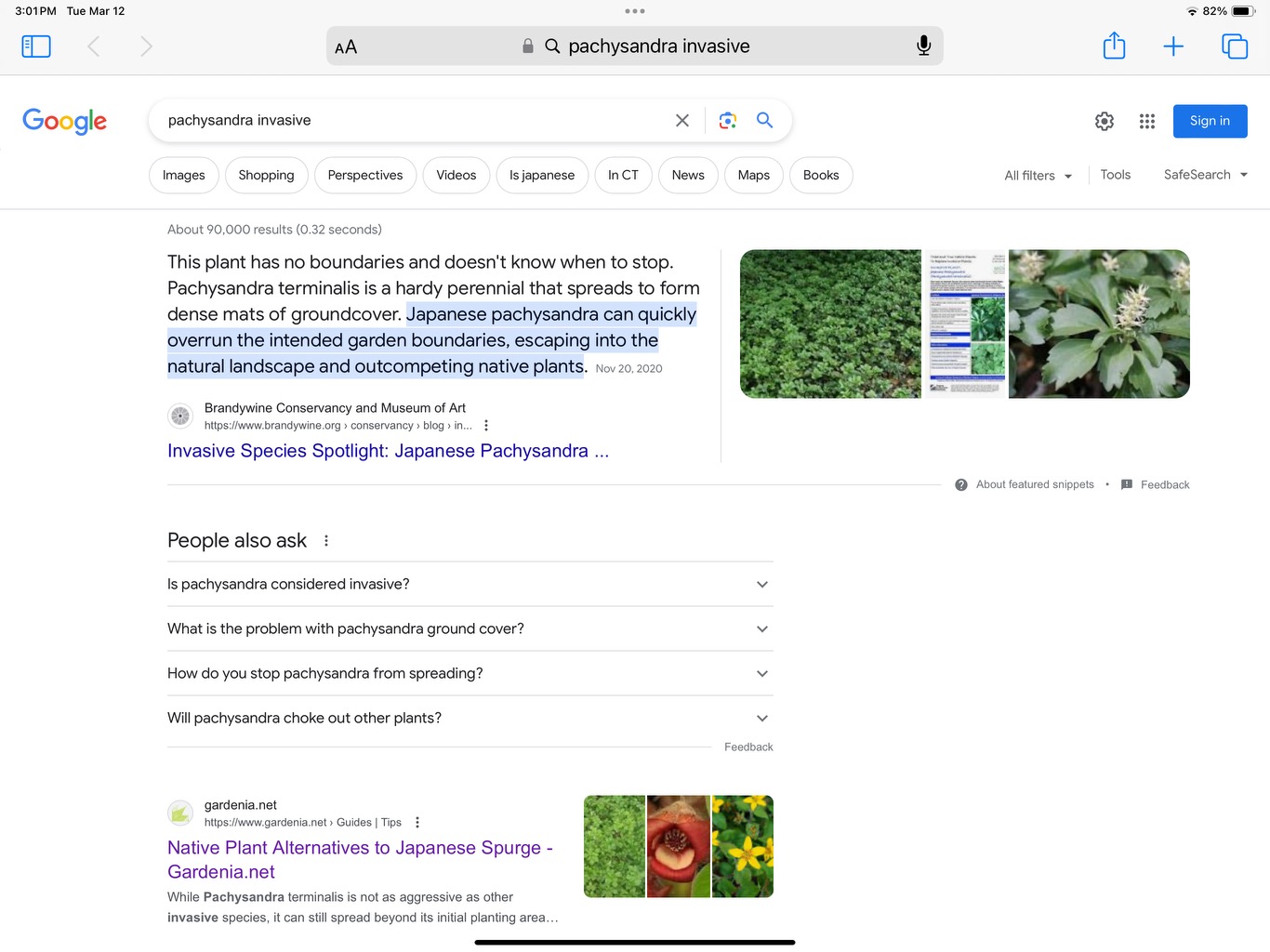

So, how do we know which plants are invasive and should be avoided?

The simplest way is to use your phone! Put the name of the plant you’re considering and the word “invasive” into Google, or whatever search engine you use, and see what happens! For example, this is the result of a .32-second search using the words “pachysandra” and “invasive”:

Seeing that result should suggest choosing a different groundcover – a native one, perhaps?

Another way to avoid invasive plants is to watch for certain buzzwords in the ads. Like most businesses, the nursery industry grabs consumer attention with ads emphasizing the benefits of a product while omitting any discussion of the down-side. As you browse catalogues and nursery labels, watch for the red flags that signal invasive plant characteristics. Words like “grows anywhere,” “fast-spreading,” and “pest free” can mean that a plant has no natural insect or animal controls on this continent.

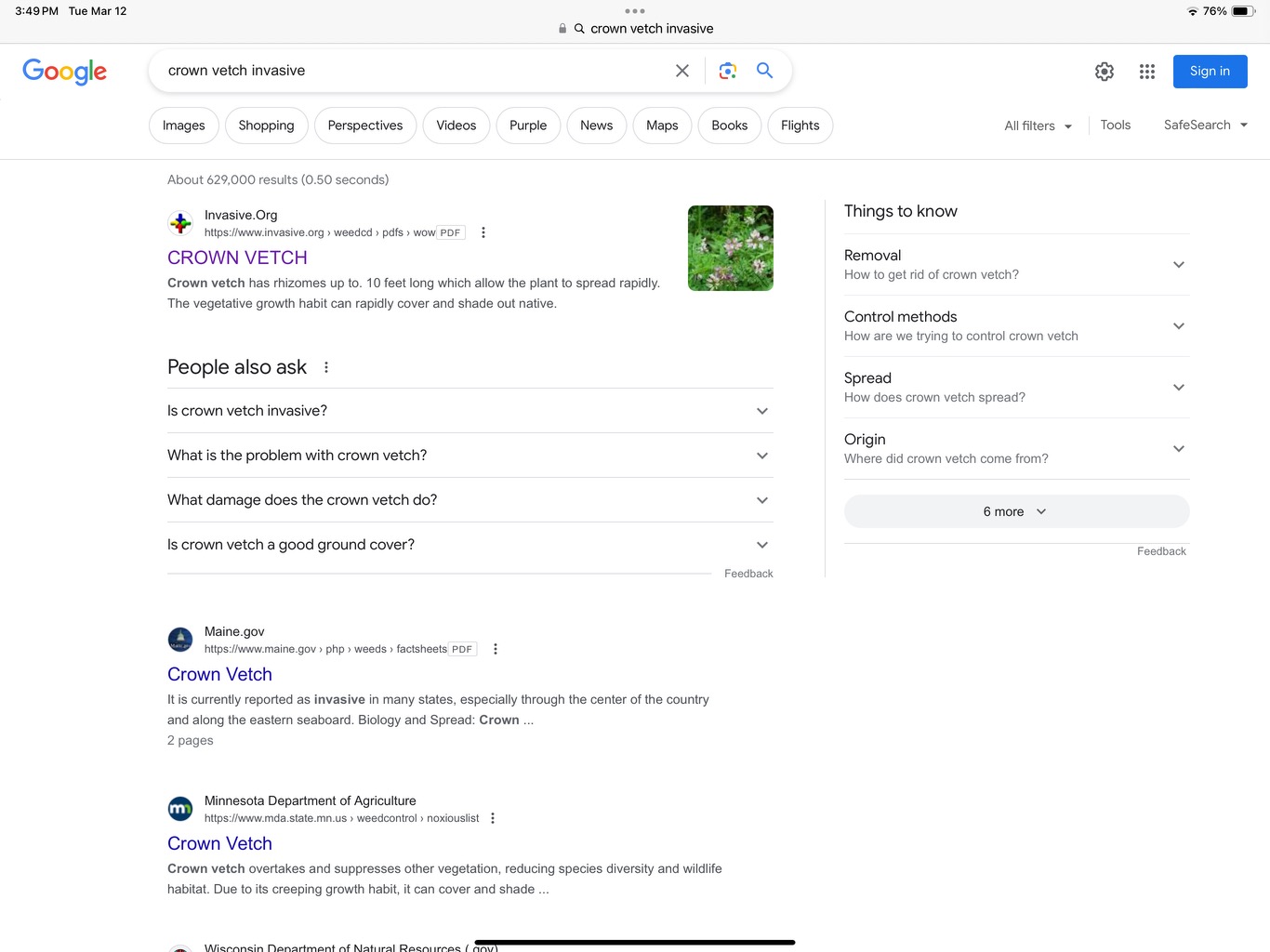

This is a great example: any plant that will grow on “steep slopes, poor soil, trouble areas, stream or pond banks,” yet is “drought resistant and sub-zero hardy,” as well as “disease and insect free” and “grows so thick it chokes out even persistent weeds and requires no mowing or care” is the very definition of an invasive species!!

A quick Google search instantly turns up the truth about the advertised plant:

At the bottom of the catalogue ad for crown vetch, there is a note that it cannot be shipped to certain states. That is another dead give-away. If any state has actually prohibited importation of the plant, it is extremely likely that the plant is invasive in many other areas as well. The political process just hasn’t progressed far enough to actually outlaw the plant in other states. Checking Invasive.org will tell the true story:

Invasive.org is a joint project of the University of Georgia and the US Department of Agriculture. They collect, review, monitor, and aggregate reports of invasive plant species that have escaped cultivation and infested natural areas. If a plant is reported as invasive anywhere in the US, it is best simply to avoid it and choose something else, preferably a native plant.

Of course, the best reason to avoid planting invasive species is to protect natural areas and critical habitat for American wildlife. But protecting the value of your own property, and sparing yourself the misery of trying to get rid of a plant you wish you had never planted, is another good reason.

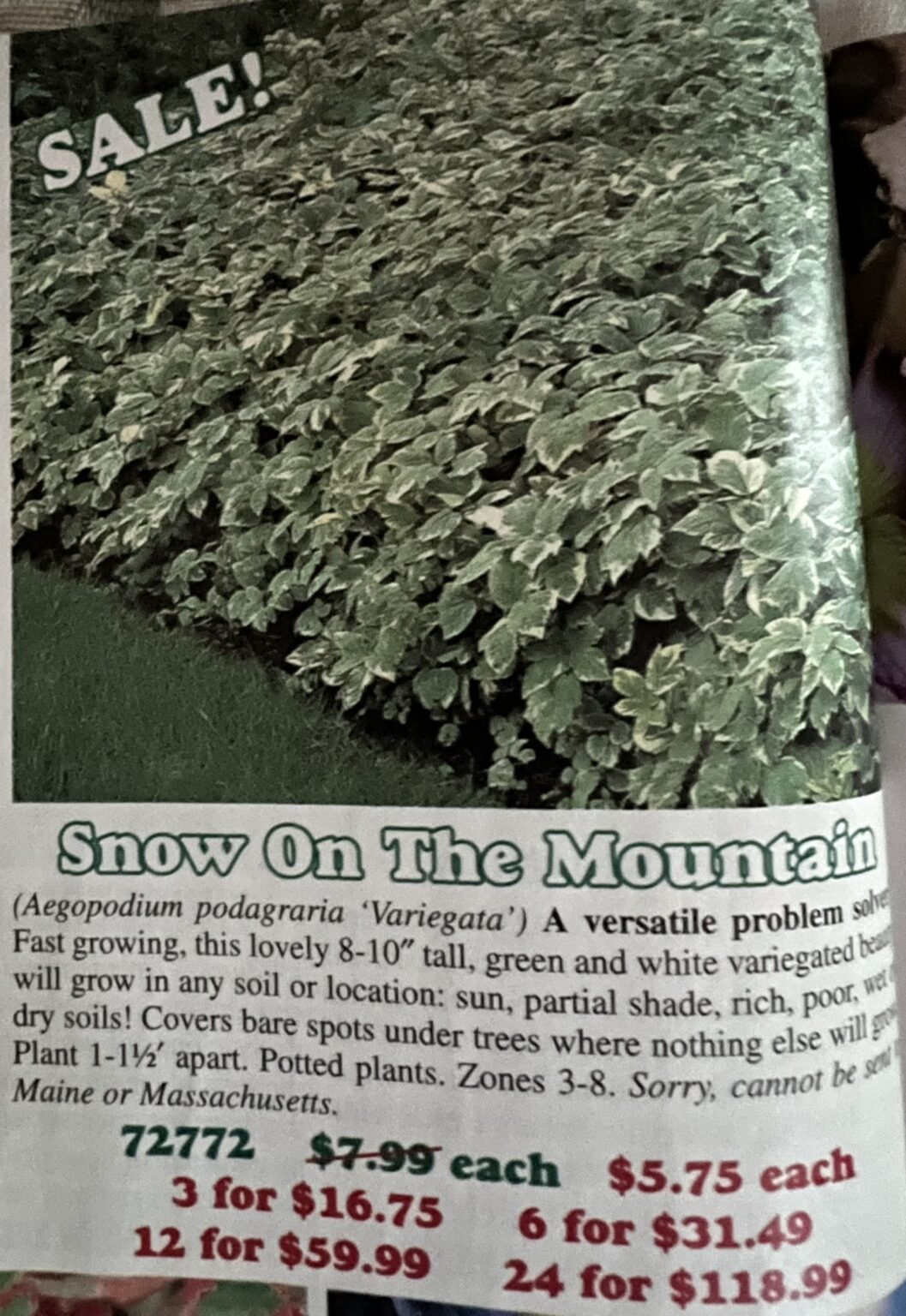

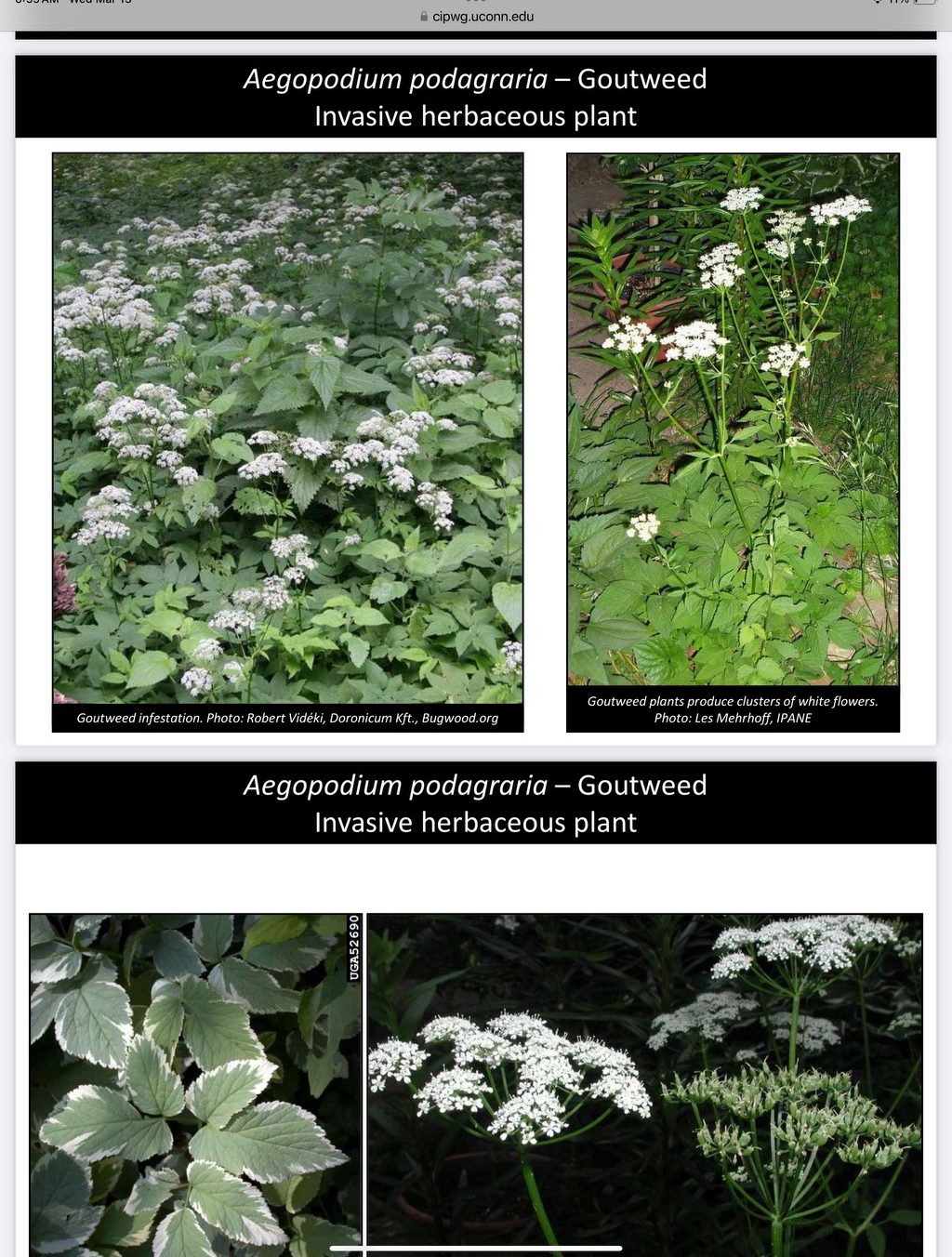

If you fell for an ad like this:

and then watched in horror as that “snowy” plant turned into a solid green mass, invading your lawn and every flower bed, you understand the meaning of regret. (We hear there is a “support group” on Facebook for people who have been victimized by goutweed!)

Other commonly sold plants that can become big regrets on suburban properties include: bamboo, Chinese wisteria, wintercreeper, Asian honeysuckle, periwinkle (vinca), Chinese silver grass, Rose of Sharon, ajuga (bugleweed), Norway maple, and of course, all forms of ivy. All of these plants can spread themselves well beyond where you wanted them and are tough to remove, creating maintenance headaches.

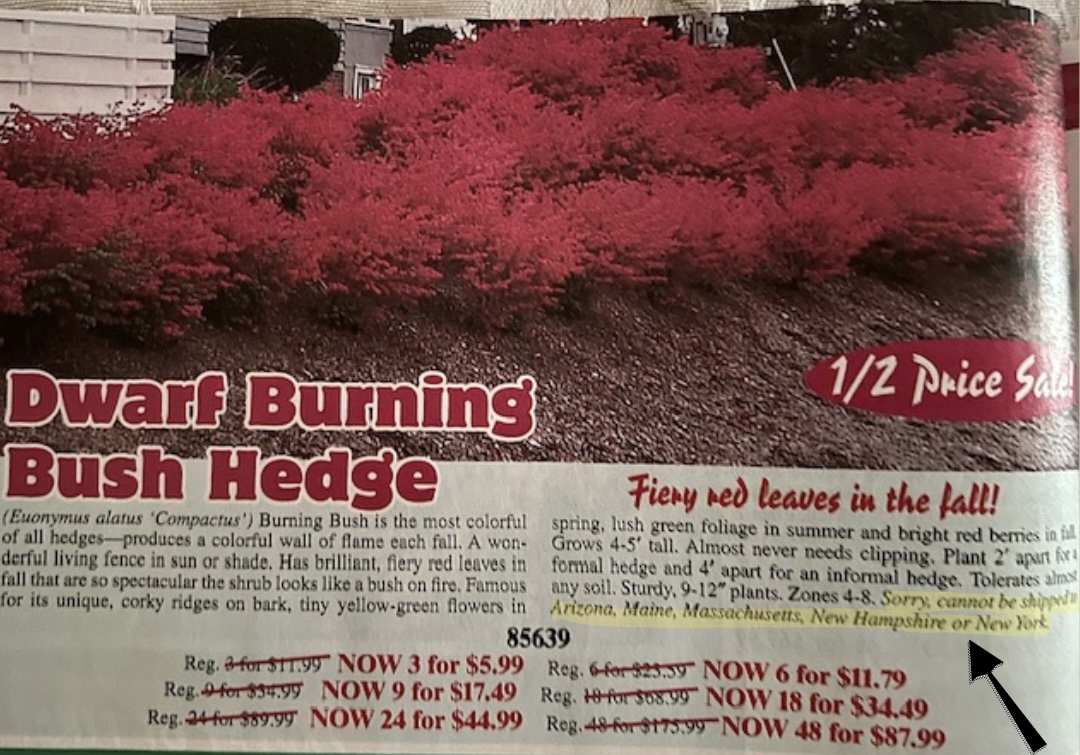

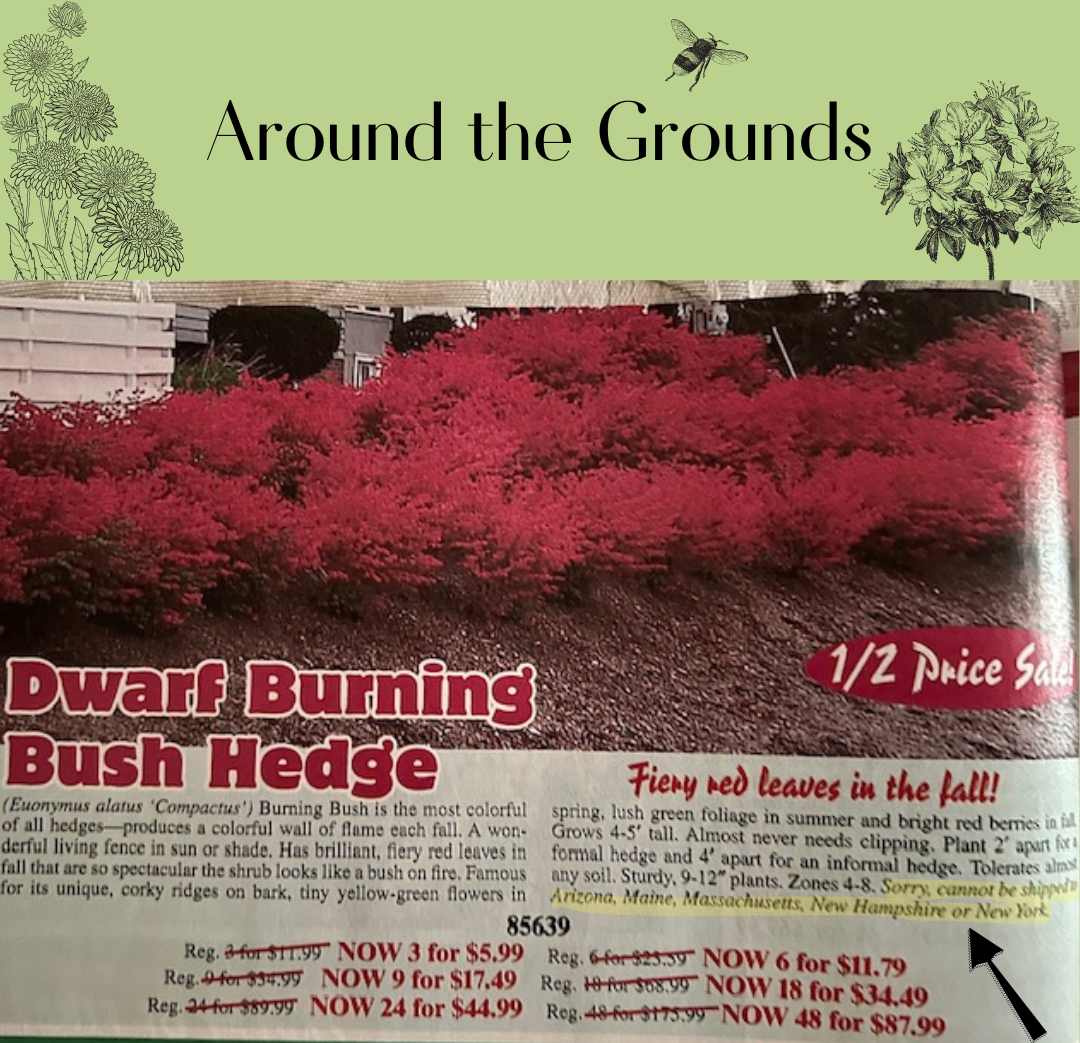

Still other invasive species may not cause trouble in your yard, but will find their way into nearby woods, parks, and natural areas: burning bush, privet, Japanese barberry, autumn olive, buckthorn, Bradford pear, tree of heaven, and Japanese spirea all spread themselves aggressively from gardens into natural areas.

There are so many excellent native alternatives to these troublemakers. Native plants do have natural controls! Birds, bees, insects, and other animals not only need native plants, their participation in the ecosystem will save you the expense and effort of battling invasive plants. Look back through the Around the Grounds Collection for lots of native plant recommendations that will work in your yard.

Happy spring gardening!

THIS BLOG IS WRITTEN BY CATHY LUDDEN, CONSERVATIONIST AND NATIVE PLANT EDUCATOR; AND BOARD MEMBER, GREENBURGH NATURE CENTER. FOLLOW CATHY ON INSTAGRAM FOR MORE PHOTOS AND GARDENING TIPS @CATHYLUDDEN.

Thank you for this educational post. For someone who has a yard with established plants, many of which are likely non-native/invasive species, what would be the best way to transition the yard back to native plants, especially if we are not sure which ones to keep?

Rachel, my apologies. I just came across your question from this past spring. Put the name of a plant into Google with the word “invasive” and make those identified invasive plants your first targets for removal. I transitioned my own yard from the traditional suburban mix of plants over a decade or so. I first removed the most troublesome invasive plants: ivy, vinca, pachysandra, and even a nasty patch of bamboo. Over the next few years, I took down Rose of Sharon and 2 big Norway Maples. I actually discovered oak saplings under the Norway Maples and they have grown a LOT since then. Then, as non-native plants died or disappeared, I planted natives, and I’ve been chipping away at the lawn replacing it with native perennials until there is very little lawn left — just pathways between planted beds. It’s a process, but a really satisfying one!

What are your thoughts on Milkweed? A friend gave me a couple of plants and they took over my yard as well as infiltrating my neighbor’s. I spent a lot of last summer pulling it out. Still not sure I got it all.

Hi, Dolores. I’m guessing that you’re talking about tall common milkweed (Asclepius syriaca), which is a very aggressive spreader. (Native plants may be “aggressive,” but are not properly called “invasive.”) Common milkweed is too rambunctious for smaller gardens — more a roadside or prairie plant. My recommendation is to avoid that species, and pull it out or transplant it to a wild area where it might fight off some non-native invasives. There are several very well-behaved garden-worthy milkweeds which will not take over, but will still provide food for monarch caterpillars. Try “butterfly weed” (Asclepius tuberosa) — low growing, pretty, and not a trouble-maker. Taller, well-behaved species like Swamp Milkweed (A incarnata), Purple Milkweed (A purpurascens), or Whorled Milkweed (A verticillata) make great garden plants. So, don’t give up on milkweed, but go for a tamer species.

Excellent info as always Cathy!

We deal with the invasive vines attacking the trees on the Bronx River Reservation year ‘round.

It’s bad when any invasives take over, but it’s heart-breaking when we see those same plants being intentionally planted in suburban yards.

Thank you for this fantastic community service! I shared this posting on the town of Greenburgh website and will spread the word. PAUL FEINER

Holy cow, I had no idea about the sheer financial impact of invasive plants. That part really got me! Also, thanks for the invasive.org resource – awesome! 🙂

Burning bush is one I see a lot and I’ve definitely heard people say “well, it doesnt spread in my yard so it can’t be that invasive!” These plants that can spread widely into natural areas can be such a big problem because it can be very hard to detect in your own garden. Thinking back to natives, are there particular plants that are especially good at “escaping” like this themselves? I know oak trees are famous for getting spread so widely by birds carrying the acorns. What are some others that might spread around and add some extra habitat elsewhere?

Great question, Andrew. The answer really goes back to the basic point that native plants have natural controls in their own ecosystem that prevent them from taking over — insects and animals make use of the native plants so they spread comparatively slowly. Some perennials are aggressive spreaders — goldenrod and ostrich fern come to mind — but they don’t out-compete other plants in large areas. Unfortunately, we are not seeing other native plants spread aggressively to create healthy habitat. While acorns are widely distributed, oaks grow slowly and germination requires specific conditions, and competition for light from established trees limits oak’s ability to spread. We would love to see oaks regenerate more freely, but the overpopulation of deer is preventing that and most other forest native plants from expanding habitat as they should. Of course, the problem there is the elimination of predators that would otherwise control the deer population. Burning bush and barberry are not eaten by deer, so the over-population of deer eating the seedlings of native trees and shrubs explains why you see the invasive plants everywhere in the woods. We can help by avoiding those plants in our yards and removing invasives in natural areas.

I love reading your posts! Great advice, well-written. Thank you!

Thank you for the kind words!

Thanks for helping distinguish “invasive” from “non-native”.

Native is always the safe choice, but there are lots of “legacy” non-native plants that have been around for over a hundred years in the US without becoming invasive — usually because they don’t reproduce themselves so successfully. Peonies, lilacs, dahlias, Oriental lilies seem to stay where they’re planted. But I always do the google check before giving the green light to a non-native just to be safe!