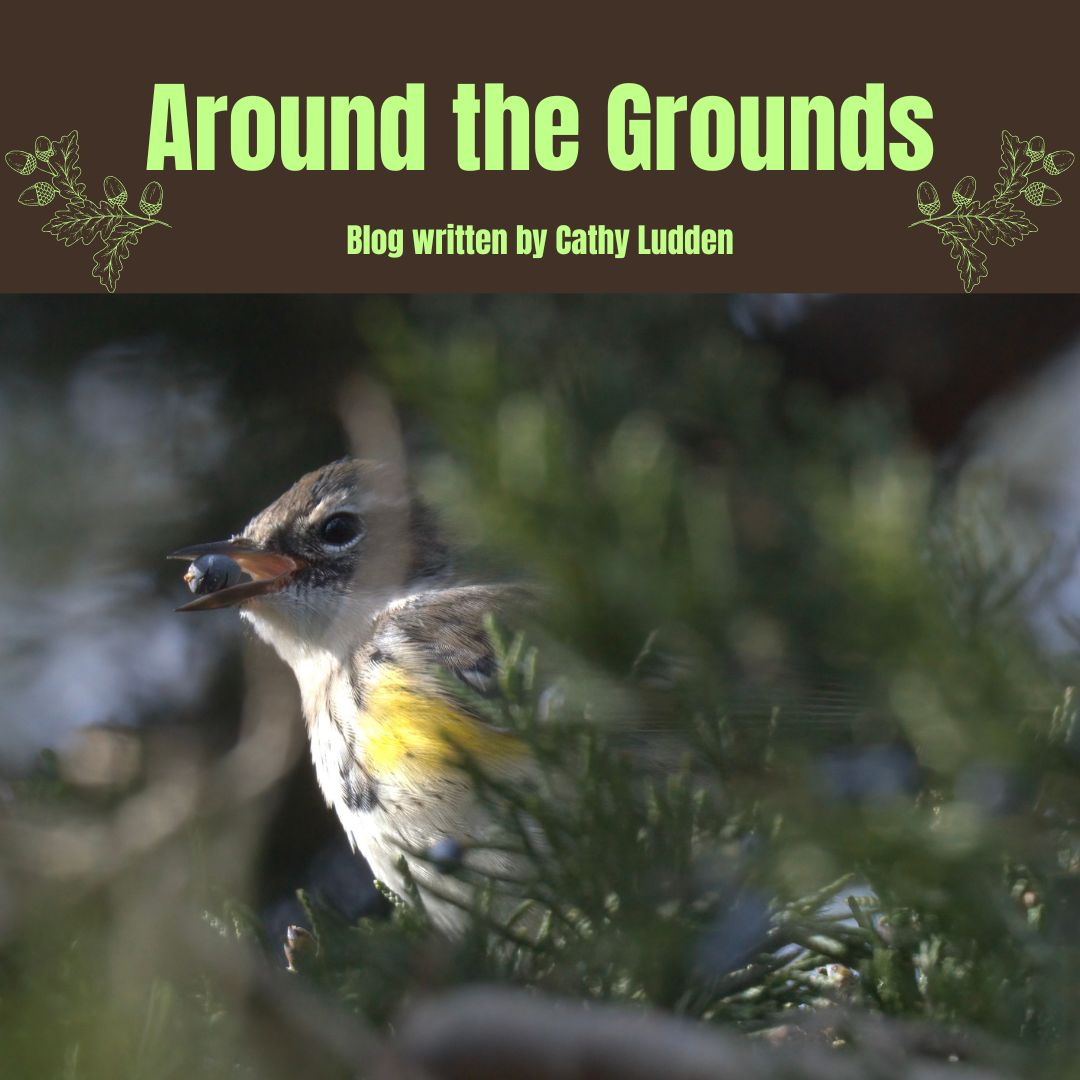

Featured photo: Yellow-rumped Warbler on Juniper — Sav DiGiorgio @Savwildlifephotography

In 1584, English explorers Arthur Barlowe and Philip Amadus were sent by Sir Walter Raleigh to investigate the North American coastline. After finding shallow water and encountering a fragrance “so sweet, and so strong… as if we had been in the midst of some delicate garden,” they landed on Roanoke Island, just off the coast of today’s North Carolina. There, they encountered the fragrant trees and described them as “the tallest and reddest cedars in the world.” Though the first settlement at Roanoke was doomed, the trees so admired by these earliest explorers proved enormously valuable to early American colonists.

But Barlowe and Amadus had the identification wrong. The Eastern Red-cedar is not a cedar at all. It is America’s most important juniper, Juniperus virginiana. Junipers and cedars both have aromatic qualities, which is probably the cause of the confusion, but true cedars are in the genus Cedrus, and not native to North America. Today, the common name of the American tree is either hyphenated (Red-cedar) or condensed to one word (Redcedar) to reduce that confusion.

The wood of Red-cedar is rot-resistant and has a natural insect-repellant quality, so colonists used it for fence-posts, coffins, and furniture. Scraps of wood chips and saw dust were useful for bedding to repel fleas and combat odors. And indigenous people shared many medicinal uses of Red-cedar bark, leaves, and berries.

But today, the most important use of Eastern Red-cedar by far is as a landscape plant. Juniperis virginiana is native to 37 states in the Eastern US from Minnesota to parts of Texas and from Maine to Florida. The tree is typically 30 to 40 feet tall, but old cultivated specimens can reach 90 feet. It is long-lived, with some trees known to be over 500 years old. It is attractive, with dark green foliage that may turn gray or bronze in the winter. And it is unbelievably tough!

Eastern Red-cedars can survive extreme temperatures from -45 degrees Fahrenheit to +105 degrees. They are also drought tolerant, salt-resistant, and tolerant of windy conditions, so they do well along roadsides, driveways, and walkways. They are not at all fussy about soil and can succeed in poor dry soil, acidic or alkaline soil, and even in swampy land. They do not need pruning, but will tolerate being clipped as a hedge or even used for topiaries! Though they prefer full sun, Red-cedars can grow in part-shade.

young trees along with scaled or whip-like foliage

Juniper leaves are needle-like and prickly when the tree is young and also on new growth, but older leaves are made of overlapping scales and are softer to the touch. The trees are dioecious, meaning male and female trees are separate plants. The female trees are wind-pollinated by inconspicuous flowers on male trees and produce small blue-grey cones that look like berries.

Eastern Red-cedar is critically important to wildlife – except deer! Deer tend to avoid the prickly, aromatic foliage, while birds flock to the grayish green waxy berries. Robins, mockingbirds, juncos, cardinals, and over 50 other bird species eat juniper berries. The dense foliage also offers winter shelter for many small animals and safe nesting sites for birds and squirrels in the summer.

The nursery industry is offering numerous cultivars and selections that make Eastern Red-cedar appropriate for a wide variety of landscape designs. A “weeping” form is called Juniperus virginiana ‘Pendula.’ J.virginiana ‘Taylor’ is tall and very narrow, almost pencil-shaped and makes a real architectural statement.

J. virginiana ‘Emerald Sentinel’ is said to bear lots of berries. ‘Brodie’ is an elegant cultivar that is narrower and smaller than the species at 6 to 8 feet wide and 20 to 30 feet tall.

With these options, it is not difficult to find an Eastern Red-cedar that will work in your landscape.

In recent years, Eastern Red-cedar has received some bad press for two reasons – both deserve mention here.

First, Red-cedar has been called “invasive” by those describing its aggressive spread into pastures, meadows, and prairies where it can replace grasses and wildflowers, eventually creating a mono-culture of Red-cedar trees. Though the word “invasive” is not appropriately used referring to a native plant, it is true that Red-cedar seedlings can quickly overcome open areas that are not well maintained. It is a “pioneer species” like aspen or yellow poplar, and will move into areas where ground is newly opened and untended.

While the unwanted spread of Red-cedar is a maintenance problem in several states in the Central and Great Plains regions of the US, it is not a concern that should prevent the wide-spread use of the tree in residential landscapes in the East. Any seedlings popping up in construction sites or roadsides here are a bonus, certainly preferable to the truly invasive non-native plants that dominate our region.

The second issue with Eastern Red-cedar is its role in the life-cycle of a native fungus called cedar-apple rust. The fungus appears in areas where Red-cedar and other junipers grow within a mile or two of apple or crabapple trees. Where apples are grown as a commercial crop, growers will avoid having Red-cedars or other junipers growing within a few miles of an orchard. Red-cedars are not usually harmed by the fungus, but the fruit of apple trees can be ruined. Commercial growers use fungicides as well as limiting the proximity of the two trees. Damage to crabapples is usually limited to yellow spots on the leaves. If the infestation is very severe, defoliation can occur.

Although cedar-apple rust is a consideration if you want to have both crabapples and junipers in your yard, the problem can be controlled by having a knowledgeable arborist apply fungicide at the correct time in the cycle. If you are growing apples for the table, adding an Eastern Red-cedar to your landscape is not recommended.

But if you ask the birds, they will strongly urge you to plant more Eastern Red-cedars!

Photo: North Carolina Extension

Love the new look of the blog! Also, found the piece regarding the fungus that Eastern Red-cedars are so crucial to the lifecycle of to be interesting – really speaks to the importance of thinking about these things in planting (unless you want to get rid of your crabapples, I guess)!

Love the updated look of the blog! Found the piece regarding the fungus that Eastern Red-cedars are so crucial to the life of – important things to consider in planning planting!

Thanks, Masha!

Just last night I was wondering ?where’s Cathy’s Blog, while I contemplate can a sustain a cedar grove on my property. Now I know I must.

Do it! They grow pretty fast, too!