“People who will not sustain trees

Bryce Nelson

will soon live in a world that will not sustain people.”

Trees convert carbon dioxide into oxygen, absorb vast amounts of stormwater, provide free cooling services, and supply food and shelter to thousands of insect, bird, and mammal species. And, if poets are to be believed, trees also soothe the human spirit.

Mature trees in a well-landscaped yard are commonly estimated to increase the value of a house by 7 to 19 per cent. Nationwide surveys show that lush lawns and flower gardens, though appreciated, do not add to house prices. But big trees suggest stability and affluence. People want to live in neighborhoods with tree-lined streets and shady avenues.

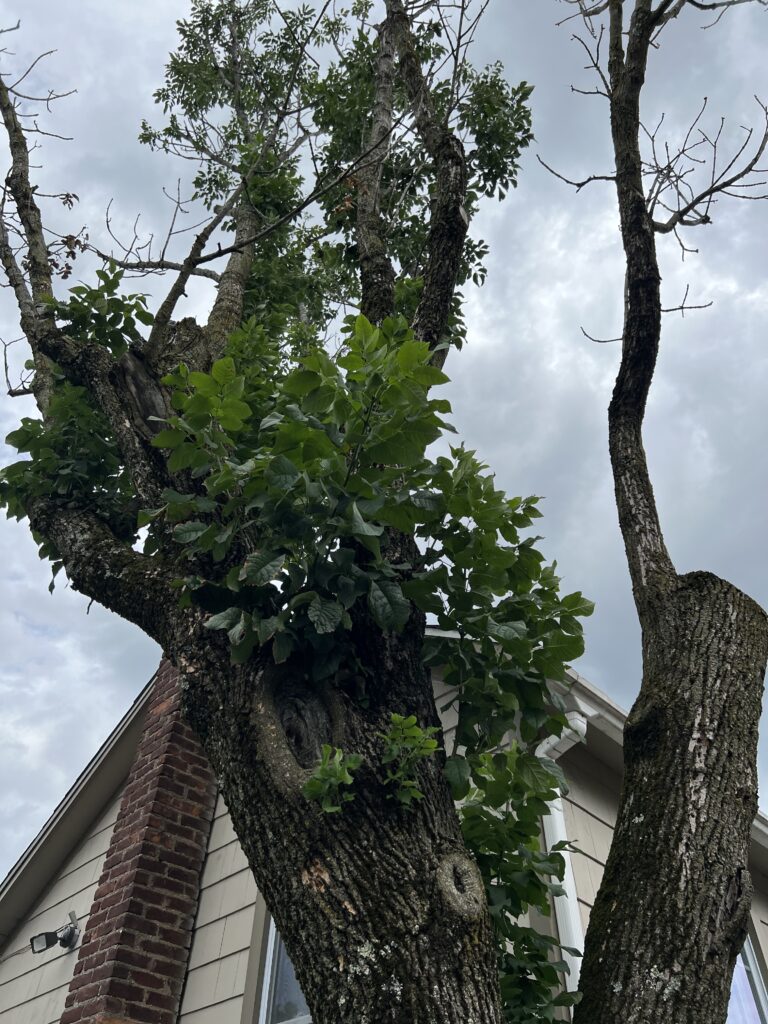

It is a tragedy, therefore, when avoidable mistakes cost the lives of these valuable friends. Too often, humans seem to forget that trees are living things with their own needs. Trees are not inanimate posts — they need air, water, sunlight, minerals from soil, and room to grow.

Misconceptions about tree roots cause many avoidable tree deaths. Unintentional damage to root structure often explains why big trees fall in storms.

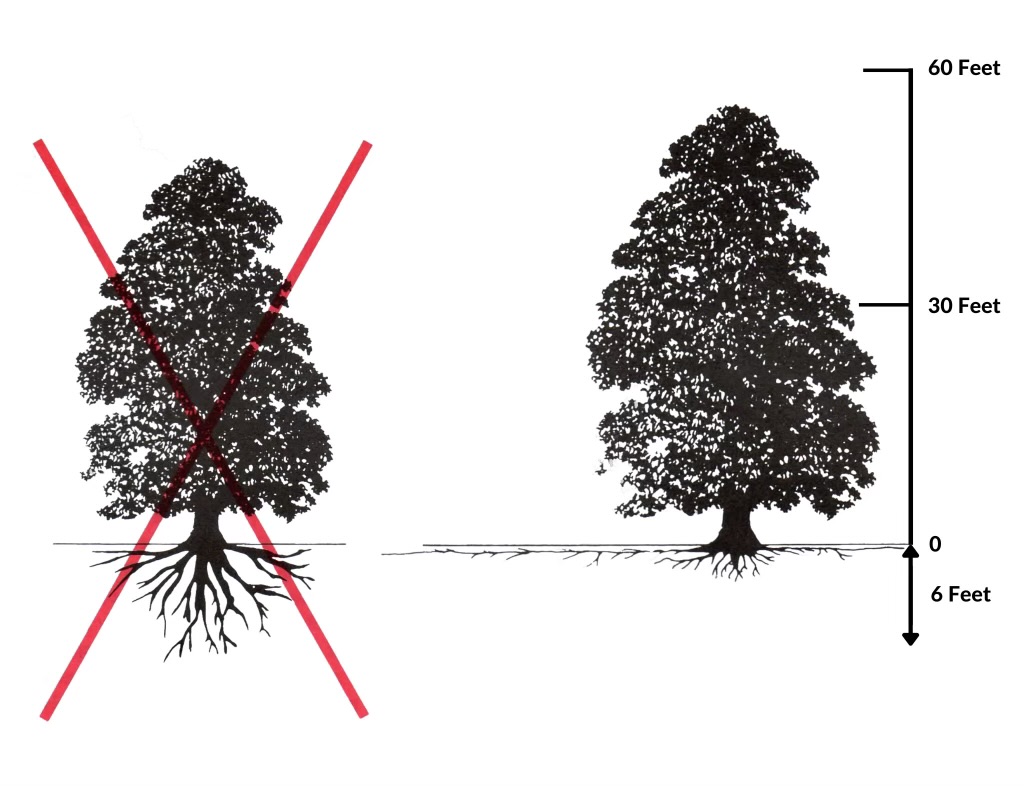

Tree roots do not typically grow downward. The soil deep under a tree is compacted, often heavy with rocks and clay, and too dense to provide the oxygen and organic matter tree roots need. So, roots actually grow laterally, angling slightly downward, but staying close to the surface. If they hit a barrier, they will turn aside rather than going deeper.

In their first few years, young tree saplings do send roots, known as “tap roots,” straight down to stabilize the weight of their branches. But even tree species considered to have deep tap roots will soon direct most of their energy into developing lateral roots. As the tree matures and the tap root reaches compacted soil, it actually recedes. The lateral roots take over, anchoring the tree with a strong, wide base. The “critical root zone” is the area closest to the tree trunk and extending to the “drip line” – essentially the circumference of the tree’s leaf canopy. The roots in the critical root zone anchor the tree and keep it upright.

When they reach 3 to 5 feet from the trunk, lateral roots begin to narrow and branch out, continuing to expand outward, ultimately reaching a distance equal to the height of the tree! These lateral roots send thousands of small “feeder roots” upward where the soil is lighter and better aerated. In fact, 90% or more of a tree’s roots are located in the top 12 to 24 inches of soil!

From “Tree Root Systems,” Martin Dobson 1995

With an accurate picture of tree root structure, it is easier to understand how homeowners inadvertently cause tree damage. Anything we do in the top 12 to 24 inches of soil, from the tree’s trunk to a distance equal to the height of the tree, affects the tree!

Here are some common mistakes we see homeowners making:

Some homeowners try to hide tree roots by building a raised planter filled with soil. But burying roots — with even a few inches of added soil — deprives delicate feeder roots of air and puts them too far from nutrients. Soil piled up around the tree trunk also damages the bark, causing it to rot and become more vulnerable to wood-boring insects. Raised tree planters may not kill a tree right away, but in a few years, the tree will decline and likely die. Damage to the critical stabilizing roots and the lower trunk make even the strongest tree likely to topple in a windstorm.

Other homeowners like to decorate around the base of trees by planting annuals there every year. Digging close to the tree year after year can result in repeated damage to roots in the critical root zone. A much better practice is under-planting with native perennials that will come back each year without requiring you to dig again. It is best to start with small plants and work carefully around delicate tree roots as you do the initial planting.

Another common reason for tree death is construction of walls, patios, and sidewalks within the critical root zone. Severing the major lateral roots responsible for stabilizing large trees increases the risk of trees falling in heavy wind.

Routine use of heavy equipment, including riding lawn mowers, can compact soil and damage tree roots. By protecting the entire critical root zone around the tree, either with under planting or good quality mulch, damage from mowers, foot traffic, and heavy equipment can be easily avoided.

With everything trees do for us, it is worth taking basic steps to save them. We should do it for the love of trees!