Have you heard all the “buzz” about pollinator gardens? It seems that community groups everywhere are planning, planting, or maintaining pollinator gardens. Schools, parks, churches, and homeowners are adding pollinator-friendly native plants to landscapes all around us. Are you involved?

The original “Pollinator Pathway” idea was to create linked gardens through urban and suburban areas so that pollinators could travel, finding what they need to survive along the way.

The concept has grown wildly and Pollinator Pathway organizations are popping up everywhere, including locally in Irvington, Hastings-on-Hudson, Dobbs Ferry, Bedford, Elmsford, and many others.

Physically connecting pollinator gardens into an actual pathway is less important than having lots of them everywhere. From big meadows to front lawn patches to container gardens on balconies, every blooming native plant helps pollinators.

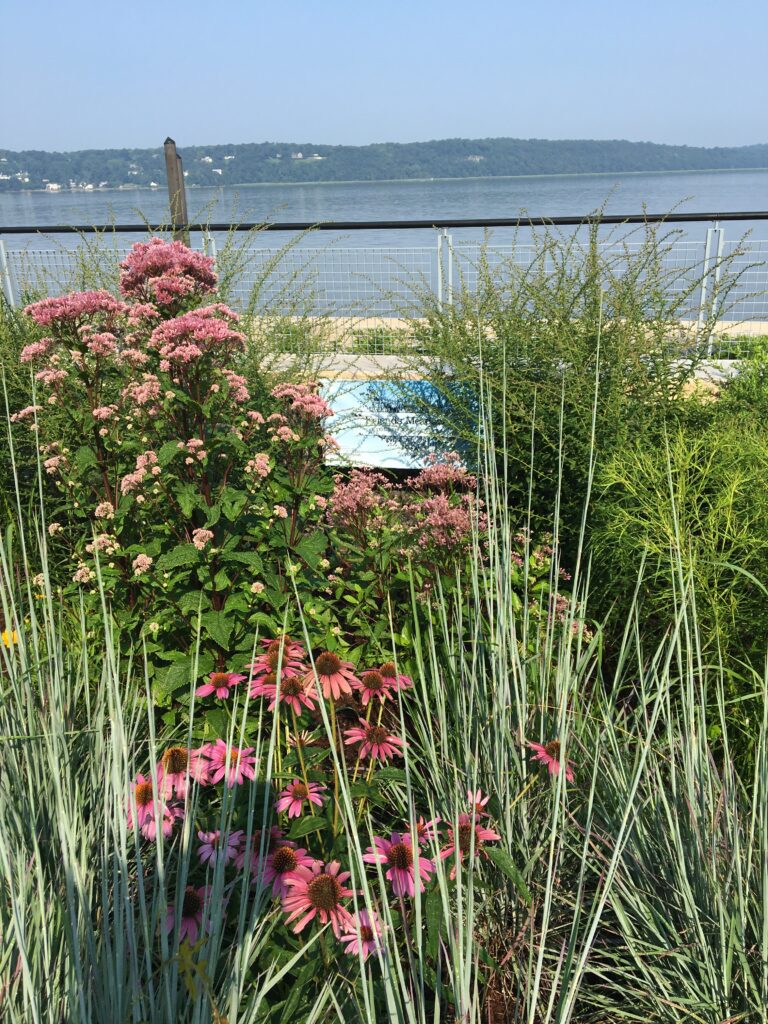

Photo: Don Vitagliano

Driving this movement is recent documentation of a stunning decline in insect populations, especially pollinators. Since many of our food crops depend on insect pollination, this is a huge wake-up call for all of us. Insecticides, agricultural techniques, and loss of habitat all contribute to crashing insect populations. And since most birds depend upon insects to feed their young, bird populations also are declining rapidly.

Unlike many other global problems, we can actually do something about this crisis — right in our own yards. Pollinator gardens are a powerful force for good. And the bonus? They are gorgeous! Every time we convert a patch of lawn, or bare dirt, or a weed-infested spot to a pollinator garden, we not only provide survival essentials for birds, bees, and butterflies, we brighten our neighborhoods with color and life.

Photo: Nancy Delmerico

Photo: Myriam Beck

So, what makes a garden a pollinator garden? Short answer: native flowering plants. The two main classes of pollinators we are trying to save are butterflies and bees, especially native bees. Bees need flower nectar and pollen. Butterflies need nectar and host plants for their caterpillars to eat. Pollinator gardens should provide all 3 essentials: nectar, pollen, and host plants.

Photo: Travis Brady

The reason we keep emphasizing native plants is because most of these insects are specialists — they depend upon one or two specific species of plants for survival. For example, there are over 20 species of native bees that can only eat the pollen of Goldenrod! And just as Monarch caterpillars can only eat the leaves of Milkweed, other butterflies’ caterpillars are also completely dependent upon specific plant species – their “host”plants.

Pollinator gardens do best in sunny spots. Butterflies and bees prefer sunshine and are more active in sunny areas. Any place that lawn grass grows is a good spot for a pollinator garden.

The best plants for pollinator gardens are native meadow or prairie plants. Adapted to harsh environments, they don’t need rich soil and never need fertilizer. Most of these plants are drought-tolerant, so they don’t need irrigation once they are established, and many are deer-resistant. And we recommend perennials rather than annuals, so the plants come back every year. It is easier, and definitely cheaper in the long run, to plant a perennial pollinator garden than it is to buy, plant, water, and fertilize annual bedding plants every year.

Spring is almost here! If you are thinking about planting or expanding a pollinator garden, there are loads of great resources to get you started. The Pollinator Pathway website linked above has how-to’s and plant lists. Watch for local native plant sales. The Native Plant Center will hold its annual plant sale this year at Westchester Community College on April 30. And the Garden Club of Irvington will have native plants for sale at the Greenburgh Nature Center on May 7, plus lots of knowledgeable help on hand.

And watch this space! Over the next several months, this blog will highlight many of our favorite pollinator plants. Come see them in action at the Greenburgh Nature Center all season long!