Winter is a tough time for our beloved songbirds. Food and shelter are more difficult to find. Food is scarce because insects, the best source of nutrition, are in short supply; and shelter, from weather and predators, is harder to find when branches are bare. Too many suburban yards, with big expanses of lawn and too few trees and shrubs, make matters worse. In this season, perhaps even more than others, we can help.

Scientists tell us that our songbirds are disappearing due to loss of “habitat” – places where food and shelter are available. Our parks, forests, and nature preserves are not enough to maintain bird populations, and there is not enough undeveloped land remaining for them. More than 83% of all land in the US is now privately owned, and 40 million acres of it is planted in turf grass, which is useless for birds. As a result, since 1970, we have lost one-third of the total bird population in the US and Canada. And the biggest losses, more than 90%, are in the once “common” bird species that should be found in our backyards!

Photo: Sav DeGiorgio

So, suburban yards are increasingly critical to bird survival. We can save birds just by landscaping our yards to provide food and shelter all year long. We can plant habitat!

Creating habitat is not difficult, and it is beautiful. Simply by planting more native trees and shrubs – lots more — and by leaving native leaves, grasses, and perennials in place all winter, we can provide a supply of food and shelter for birds while making our yards more interesting and attractive.

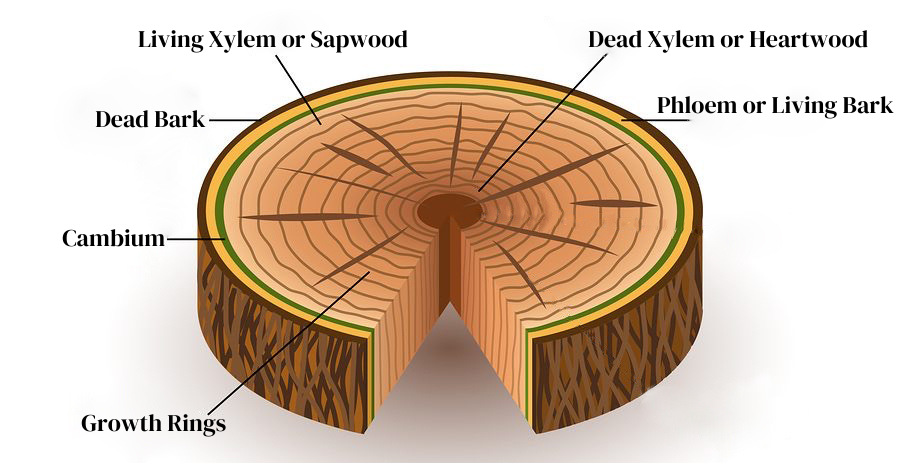

The bark of native trees – including oaks, birches, hickories, and white pines – hides over-wintering insects and becomes a hunting ground for many birds in winter. Chickadees, Nuthatches, and Woodpeckers all prowl tree bark looking for food.

Photo: Sav DeGiorgio

The leaves that fall from native trees, especially oaks, hide seeds and insect larvae essential for birds’ winter survival. Allowing fallen leaves to remain under trees and on perennial beds all winter, rather than blowing and bagging them for disposal, provides a continuing food source for songbirds.

Native trees and shrubs with berries feed birds and add winter interest to the landscape. Winterberry, Common Juniper, and American Holly liven the garden with berries that birds love.

Photo: Sav DeGiorgio

Photo: Sav DeGiorgio

The simple decision to leave ornamental grasses and flower stalks standing all winter, rather than cutting them down, is an easy way to provide food for winter birds. The changing colors and shapes of the plants are beautiful over the season, and birds will be frequent visitors there.

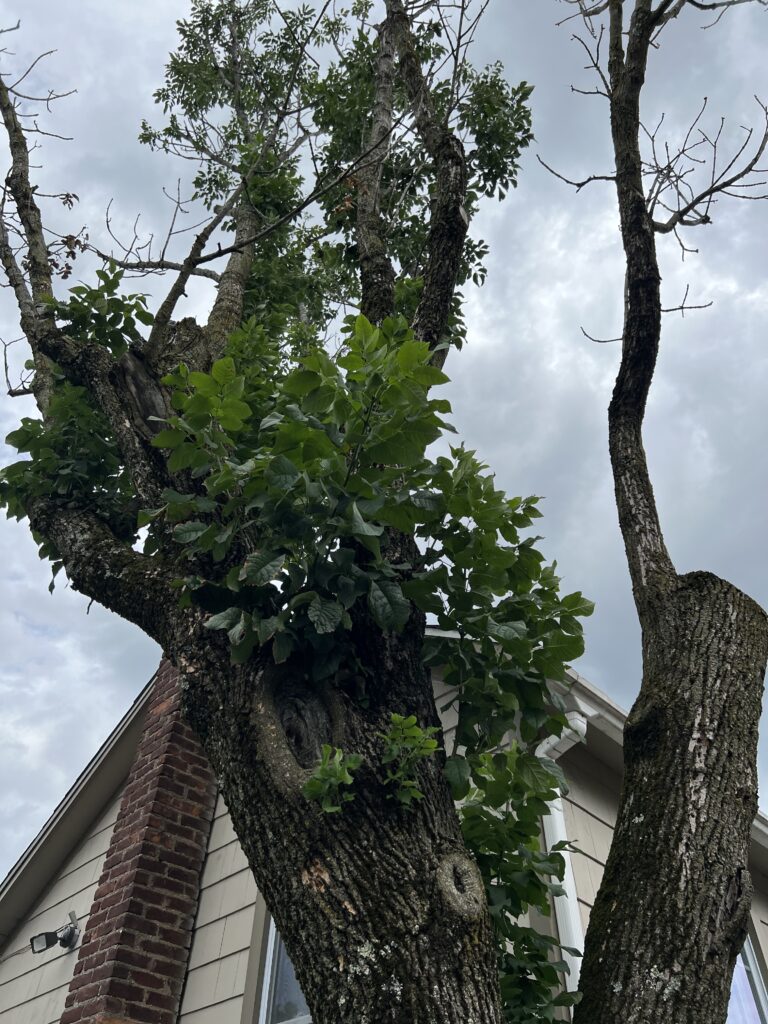

Winter birds also need shelter – places to hide from predators and to huddle in freezing temperatures. Open lawn, with a few tightly clipped shrubs, offers no protection.

Instead, a yard heavily planted with trees, shrubs, perennials, and grasses is the place birds want to be. Evergreen trees and shrubs offer great hiding places. Rhododendron, Mountain Laurel, Leucothoe, Juniper, and Inkberry are beautiful evergreen shrubs birds will appreciate. Deciduous shrubs that form a thicket of dense, twiggy stems, even without leaves, protect songbirds from hungry hawks. Shrubby St. John’s Wort, Dwarf Fothergilla, Winterberry, Bayberry, Oakleaf Hydrangea, and Virginia Sweetspire are all good examples of native shrubs that provide both seeds and hiding places in winter.

Many of us try to help birds by setting up backyard feeders. But most birds won’t stay out in the open while they feed. They “grab and go.” If you want birds to frequent and benefit from your feeder, you’ll need trees and shrubs — a thicket – nearby where they can hide while they eat.

Photo: Eric Rothenberg

Planting habitat for birds in our own yards is no longer optional – it is urgent! We are running out of time. Bird counts in 2022 show that populations of more than half of all US bird species are continuing to decline. Birds are disappearing because they have nothing to eat and nowhere to hide. Suburban gardeners and homeowners can make a difference if we act now.

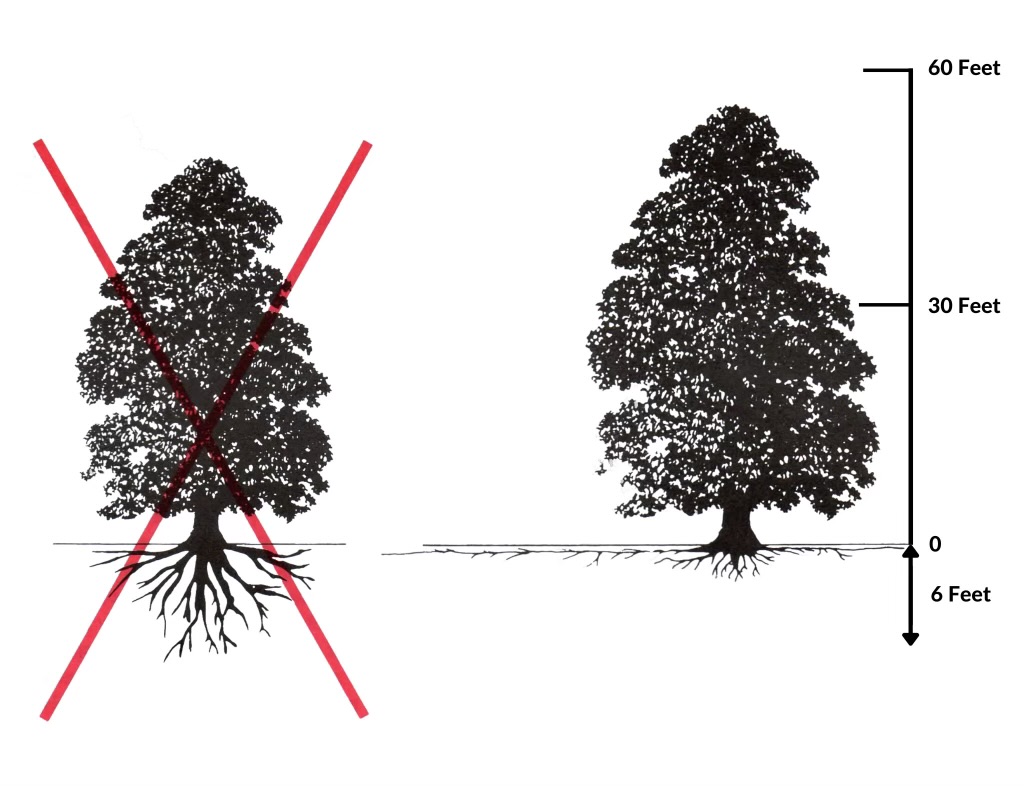

We must go from this:

To this:

A special thank you to Sav DeGiorgio, Arborist for the Parks and Recreation Department of the Town of Greenburgh, for his beautiful bird photographs! See more of Sav’s photography on Instagram: @savwildlifephotography