Suburban yards are places for families and friends to relax, perhaps enjoy a barbecue, and watch children and pets play safely. Privacy is important.

No wonder, then, that suburban homeowners often decide to plant a “privacy screen.” Hedges of trees or shrubs, planted as living “green fences,” are as common in suburbia as the lawns they typically surround.

But too often, these hedges are made with invasive plants that spread themselves into natural areas causing ecological harm. Top offenders include privet, Japanese barberry, forsythia, bamboo, and burning bush. All of these plants are recognized as invasive species and should be avoided.

The good news is that the need for privacy does not require bringing any of these offensive plants onto your property. There are so many better choices!

In the Eastern US, the most popular privacy screen by far is Arborvitae (Thuja occidentalis), also known as Northern White-cedar. Favored by builders and landscape maintenance companies, a row of inexpensive and readily available Arborvitae is often planted along the property line as soon as a new house is built.

Though Arborvitae is a much better choice than any of the invasive plants mentioned above, it is not the only — or best — option. In areas populated by deer, Arborvitae is extremely vulnerable.

Here are some alternatives – beautiful evergreen trees and shrubs, native to the Northeast, that make ideal privacy screens. And because they are native, they also offer value to native birds and pollinators!

American Holly (Ilex opaca) makes a dense, evergreen privacy screen and has the bonus of tiny flowers for pollinators in the spring and beautiful berries that add winter interest to the landscape.

Rhododendron is another good choice for privacy. When European settlers first explored the Eastern US, they struggled through massive stands of Rhododendron maximum that formed impenetrable evergreen thickets. Why not use that same feature now as an effective screen? Our native songbirds love to hide in a thicket!

Inkberry (Ilex glauca), another native evergreen, grows quickly and has shiny, dark green leaves that form a dense screen. More winter-hardy than boxwood and growing taller, Inkberry is a great hedge plant.

Grass

The very best privacy screen, though, is not a row of one species of plant, but a forest! The Northeastern US was once predominantly forest, and many of the plants in those forests are still the best plants to grow here. In suburban yards, we can mimic the beauty, seclusion, and peaceful quiet of a diverse forest simply by planting more stuff! And a bigger variety of that stuff is inspired by our native forests!

Maybe it’s time to reconsider our approach to the “privacy screen.”

Hedges can be great, but they can also be visually boring and ecologically sterile. There is no law requiring homeowners to mark their property boundaries with a row of identical plants. Just because your property line forms a rectangle doesn’t mean your landscape has to be one. A diverse mix of plants – native trees, shrubs, grasses, and perennials – planted in masses makes a landscape interesting, lush, ecologically valuable, and very private.

Rhododendron completely screens a house from the road

If you already have a hedge or a fence along the property line, consider planting inside it using a mix of native trees and shrubs that change with the seasons. Start with the corners.

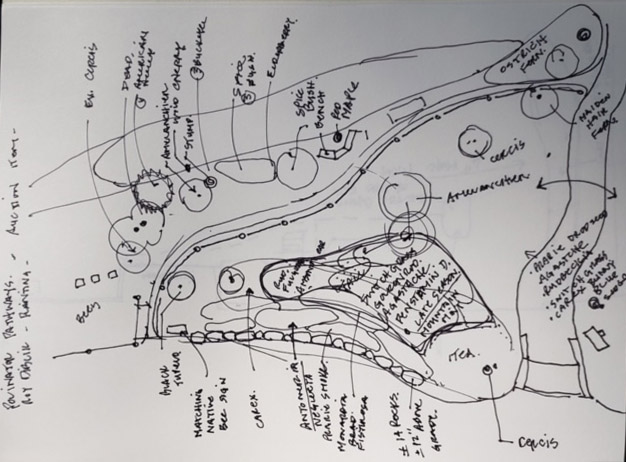

Trained landscape designers tend to avoid square corners and straight lines in their designed plantings. You can do the same thing. Map out curved beds that soften the corners and bring more plants further into your yard. Plant taller shrubs at the back, and choose flowering shrubs and perennials to plant in the foreground where you can enjoy them.

So, consider creating a privacy screen that looks more like a forest than a fence. By planting more plants, and a bigger variety of plants in more of your yard, you will have more privacy, more seasonal interest, less lawn to tend, and more habitat for birds, butterflies, and fireflies.

How’s that for a win-win-win-win?!