You may already know that monarch butterflies need milkweed. But did you know that milkweed does not need monarchs? Milkweed is not pollinated by monarch butterflies!

Monarchs have long skinny legs, and even longer skinny tongues. They have learned, over eons of co-evolution with milkweed, to avoid the dangerous sticky sap of milkweed by carefully alighting on the sides of the flowers and lowering their long “tongues” (proboscises) into the flower to reach the sweet nectar.

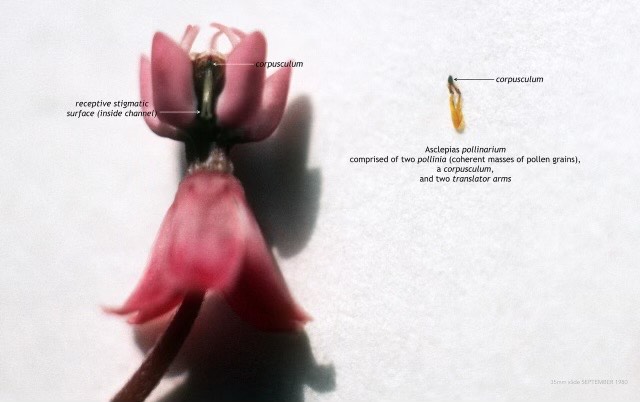

As they drink, monarchs are careful to not put their feet down inside the flowers where they might get stuck. Unfortunately for the milkweed, this means that monarchs don’t pick up milkweed pollen! The pollen is held in specialized structures inside the upper portion of the flower called “pollinia.” For pollination to occur, pollen from the pollinia has to reach the flower’s stigma, deeper inside the flower. Without successful pollination, no seeds develop, and milkweed does not reproduce.

Graphic: Rick Darke

So, if not monarchs, who pollinates milkweed? It’s not any of the other butterfly species that also visit milkweed flowers without picking up pollen. Honeybees can’t do it. They are native to Europe where milkweed isn’t native, and they are too small to be strong fliers. If they go deep enough into milkweed blossoms to reach the pollen, they can be trapped, which is not good for either the bee or the milkweed.

Milkweed needs a strong flier, with stout hairy legs that will go down into the flower, catch the sticky pollinia, and carry pollen from one flower to the next. Luckily, nature has provided just the right insect for the job: carpenter bees!

Photo: Pixabay

Carpenter bees (Xylocopa spp.) are the most important pollinators of milkweed. Their legs are heavy and hairy, so they can step right into the flower and come out covered with sticky pollinia. They are strong fliers, so they do not get trapped, and they can carry the excess baggage. As the carpenter bee goes from flower to flower, pollen is dispersed, flowers are pollinated, seeds form, and milkweed is reproduced.

Photo: Polinizador’s Blog

Recently, friends who were developing a new pollinator garden for a historic property commented on the trouble they were having with carpenter bees burrowing into the eaves of the historic building. They said that exterminators had tried several applications of pesticide over the years, but the bees were nesting once again in the wooden structure.

Only later, when we learned of the connection between carpenter bees and milkweed, did we realize the contradiction! If we plant milkweed for monarchs in a pollinator garden, but then try to kill the carpenter bees nesting in the eaves of the house, we are pulling a thread in the complex web of life that can unravel the whole thing! If we kill carpenter bees, milkweed disappears. If milkweed disappears, so do monarchs.

When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.

John Muir, Naturalist

So, what to do about carpenter bees? Well, they prefer to move into holes or cracks that are already established. They apparently don’t like the smell of citrus, and they don’t care for white paint. So, instead of pesticide, try filling existing holes and cracks or replacing weak structures. Apply citrus oil, or maybe re-paint. But killing them? They are definitely hitched to everything else in the universe.

So, it is complicated. Nature is complicated. The more we learn, the better we understand the profound relationships among living things that co-evolved over millennia.

But that doesn’t mean it is difficult to do the right thing. If we simply start with the maxim “do no harm,” we can make better choices. Before we kill a “pest,” let’s understand that creature’s role in the world. Let’s avoid pesticide, apply fewer chemicals, plant native plants, plant more plants, allow a little mess for habitat, live and let live.

For more information on the complex relationship between milkweed and the insect world, see the post “ Marvelous Milkweed-Not Just for Monarchs!” linked here.