What makes a plant, or a whole landscape, “drought tolerant”? Why do some plants need water regularly while others are fine without it for weeks or longer? Drought tolerance depends primarily on two factors:

The first is where a plant evolved. Adaptation to particular environments happened over millennia, and most plants will thrive only in conditions very similar to those where they evolved. That is why, when considering a plant for our gardens, we always want to know whether it is native to our region. Plants that evolved in tropical rainforests will never be drought tolerant. On the other hand, plants that evolved in America’s open meadows are well-adapted to life under baking sun with occasional torrential thunderstorms. Those plants can withstand weeks of heat and drought still looking great, and then stand up to the floods that so often follow.

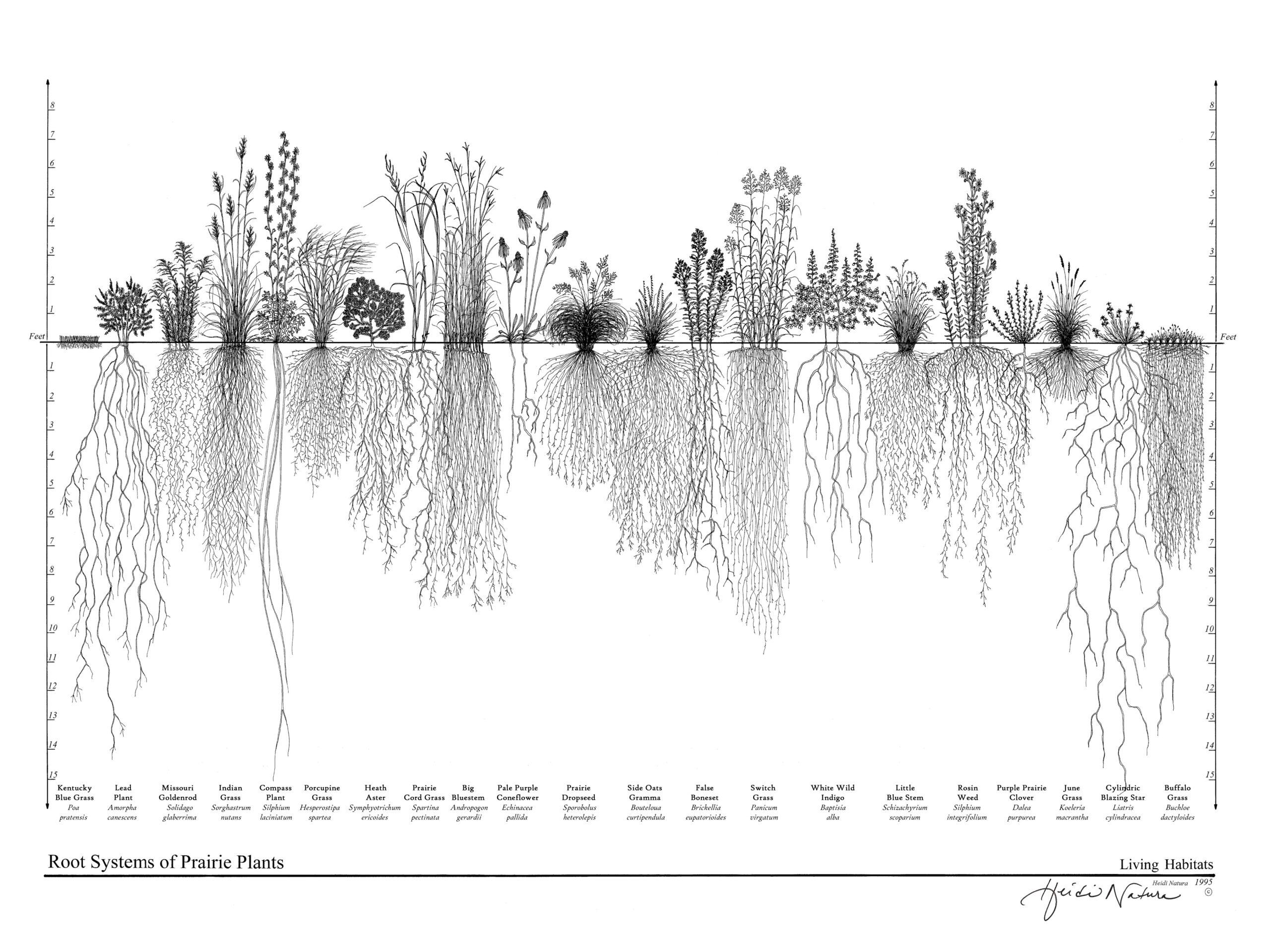

The second big factor in drought tolerance is root depth. Plants that evolved in wet climates usually have shallow roots. Plants that evolved in hard-packed prairie have strong, deep roots that force their way down through poor soil to reach and hold any available water. They can withstand long periods of drought. They also can absorb flood water because their roots break up the soil, allowing water to penetrate rather than run off.

Graphic used with the permission of artist

As the chart above indicates, many plants that evolved in America’s prairies like Goldenrod, Coneflower, Prairie Dropseed, Switch Grass, and Wild Indigo have very deep roots, reaching down 4 to 8 feet! As a result, they make great garden plants because they are both beautiful and very drought tolerant.

In contrast, lawn grass is not at all drought tolerant. Despite its name, Kentucky Bluegrass is not from Kentucky. It is native to mild climates in Europe and Asia. Lawn grown from typical seed mixes has very shallow roots, about 2 inches deep. Shallow roots do not retain water, so lawn needs frequent irrigation, and in heavy rain, excess water runs off rather than being absorbed and held in the soil.

But Americans love lawns. Perhaps perfect lawns and tightly-manicured shrubs became a status symbol in America because of our historic connection with England, where 19th Century aristocrats demonstrated their wealth by employing countless servants to hand-cut lawn and trim elaborate hedges.

Maybe it’s time for a change of fashion? Here is a photo of that same 19th Century landscape this summer:

Photo: Lawrence Siskind

Most of Europe is suffering from heat and drought this summer, and watering restrictions are now in place. Because lawn requires so much water and retains so little, lawn irrigation is usually the first target of water regulation. In the US, lawn watering (not agriculture!) uses an average of 8 billion gallons of water daily – that’s 32 gallons for every man, woman, and child in our country, every day! (Tallamy, Nature’s Best Hope) Clearly, our love for lawns is not sustainable.

Restrictions on residential landscape watering have been a reality in California and many of our Southwestern states for years now. So, it makes sense that landscape fashion there has rejected big expanses of lawn, and turned instead to drought tolerant native plants.

Prolonged periods of drought and low reservoirs are becoming common in the Northeast as well. Watering restrictions were imposed this summer in much of the Hudson River valley. So, it’s time to think about changing landscape fashion here, too. We can reduce our demand for water by replacing at least some of our lawn area with native trees and drought-tolerant shrubs.

By planting drought-tolerant native perennials, we can replace even small areas of lawn with color and flowers for pollinators.

Modern American landscapes need to be resilient as well as beautiful. As we rethink landscape fashion, we recognize that there is as much beauty in a vibrant drought-resistant garden as there is in a bare expanse of thirsty lawn.

For information on drought-tolerant perennials, download the plant list we used for the Nature Center’s pollinator garden here.