Pokeweed. You’ve probably seen this plant on roadsides, vacant lots, along hiking trails, and maybe even pulled it out of your own yard. It’s definitely a weed, and either a curse or a curiosity depending on your point of view. Considered a dangerous and poisonous plant by some, and a nutritious and delicious plant by others, we think of it as a valuable food source for over 30 species of native birds.

Phytolacca americana is commonly known as Pokeweed, Polk weed, Pokeberry, Poke root, Virginia poke, Poke sallit, Poke salad, Redweed, Redberry, Pigeonberry, Pocan bush, Red ink plant, and at least a dozen other names. As is often the case, the number of common names for a plant indicates the variety and duration of human experience with it. Pokeweed has a long and complicated relationship with humans.

Pokeweed is native to most of the US and is found now in all but a few states. It can reach 6 to 10 feet tall, spreads both by seed and rhizomes, and has a very deep tap root. It is a perennial that can live in a wide variety of conditions, which makes it a rather successful weed.

Indigenous peoples used Pokeweed for medicinal purposes and as a dye, especially for painting their horses. The name “poke” may come from the Algonquian word “pocan,” meaning red dye. American colonists fermented the deep magenta juice of the berries to make ink. There are preserved letters from Civil War soldiers written in Pokeberry ink, which was much more available to them than imported ink.

There is common agreement that all parts of the plant, if eaten raw, are toxic to humans and livestock, but agreement ends there. Some writers claim that Pokeweed is so poisonous it should not even be touched without gloves. Yet in most of the Southern US, Pokeweed has been hand-harvested as a staple of the local diet for generations. Some authorities say the root is the most poisonous part of the plant, and the berries are the least so. Other authorities say the berries are the most toxic part of the plant and eating even a few may be lethal. Many articles claim that Pokeweed poisoning can cause death, but after surveying historical records, a recent report found only 2 deaths from Pokeweed over a couple hundred years, and noted that one of those deaths was more likely caused by the medical treatment of the time, blood-letting.

The role of Pokeweed as part of Southern US culture is memorialized in the song “Polk Salad Annie” written in 1968 by Tony Joe White and made popular by Elvis Presley.

“Everyday before supper time, she’d go down by the truck patch

Tony Joe White

Recognizing that Pokeweed is indeed toxic if eaten raw, recipes for polk salad, or poke sallit, require boiling the tender young leaves at least twice, and with two or three changes of water. The boiled greens are then sauteed in bacon fat and eaten like spinach or collard greens. Poke sallit festivals are still part of local traditions in the South every spring. But other than those circumstances, we do not recommend eating any part of Pokeweed, and children should be warned away from the berries.

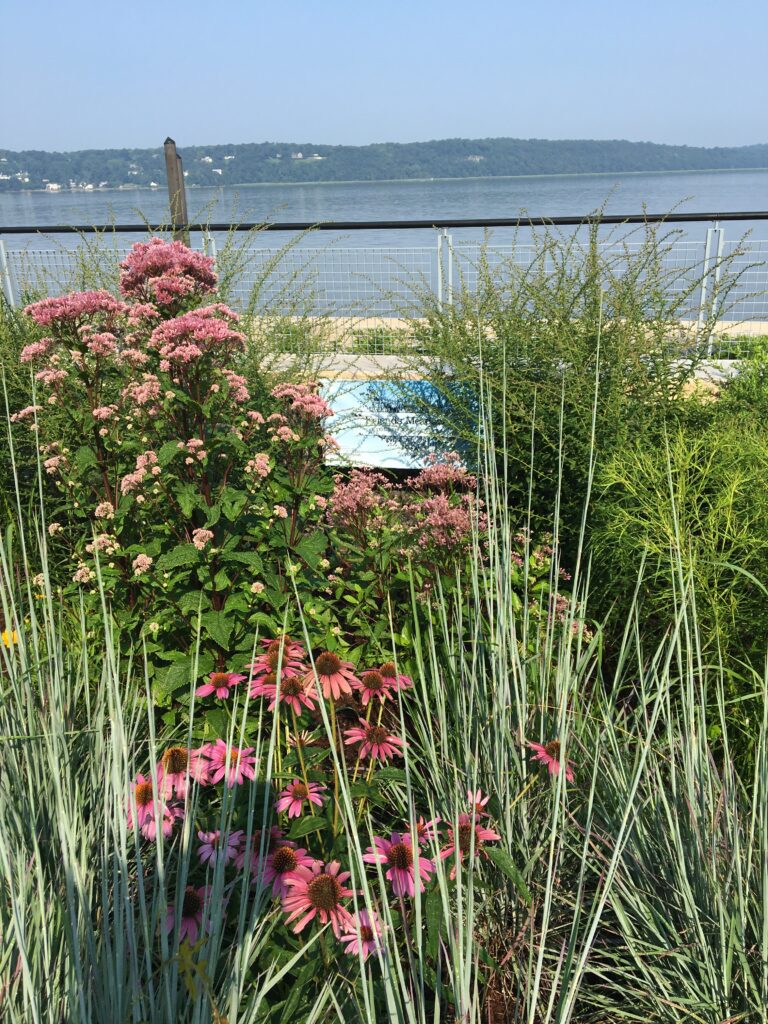

We do suggest letting the plant live if you find it in an out-of-the-way spot in the garden. Pokeweed provides a real service to our native songbirds. Migrating birds store energy from eating ripening Pokeberries as they begin their journeys, and winter birds will eat the dried berries for as long as they last. Cardinals, mockingbirds, blue jays, robins, catbirds, bluebirds, mourning doves, and over 20 other species of native birds love Pokeberries. Squirrels, chipmunks, and other small mammals do, too.

Pokeweed is interesting to watch, and it will definitely attract songbirds. So, if there is a spot near you where Pokeweed appears, we hope you can allow it to live its weedy, but useful, life.

For the birds.