Are you thinking about what to plant in your garden this year? Nurseries are already displaying their new stock, and native plant sales are popping up everywhere. It’s time to make your shopping list for spring planting. And we can help!

Over the past few seasons, “Around the Grounds” has recommended some great native perennials that will bring life to your garden. Here are some of our favorite flowering plants — with links to blog posts containing photos and tons of information about each of them:

For Sunny Gardens

Sneezeweed (Helenium autumnale) – late bloomer, hot colors

Goldenrod (Solidago spp.) – fall bloomer, essential for pollinators

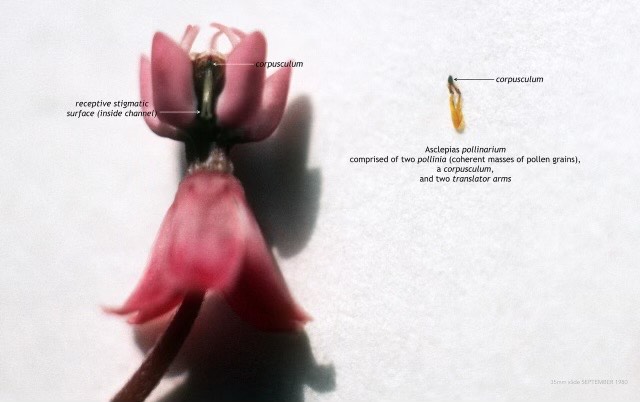

Milkweed (Asclepius spp.) – long bloom time, critical for Monarchs

Golden Alexander (Zizia aurea or aptera) – blooms early and long

Blue False Indigo (Baptisia australis) – long-lived, shrub-like spring bloomer

Mountain Mint (Pycnanthemum spp.) – fragrant long bloomer

Joe Pye Weed (Eutrochium spp.) – tall butterfly magnet

Anise Hyssop (Agastache foeniculum) – long-blooming butterfly favorite

White Turtlehead (Chelone glabra) – late blooming bumblebee favorite

Cardinal Flower (Lobelia cardinalis) – red spikes for hummingbirds

Coral Bells (Heuchera villosa ‘Autumn Bride’) – deer-resistant hosta substitute

Bluestar (Amsonia tabernaemontana) – shrub-like, blooms early

For Shady Gardens

Native Bleeding Heart (Dicentra eximia) – long bloomer, hardy

Goatsbeard (Aruncus dioicus) – large, showy white flowers

Pink Turtlehead (Chelone lyonii) – shrub-like with pink flowers

Wild ginger (Asarum canadensis) – low ground cover, hidden flowers

Golden groundsel (Packera aurea) – shade/sun flowering groundcover

Creeping Sedge (Carex laxiculmus) – clumping grass that stays blue all winter

Violets (Viola sororia) – early flowering groundcover

All of these plants evolved in our region, are well-adapted to our soil and weather, and support native insect and bird populations. Many are deer-resistant and drought-tolerant. You can learn more about their favorite garden conditions in the linked blog posts.

We’ve also recommended ferns, grasses, shrubs, and trees, so browse older posts by clicking on the “Around the Grounds Collection” button below.

Happy spring shopping! And if you live in the Greenburg, NY area, mark your calendar for our spring plant sale on May 13 where many of these plants will be available.